What was the Enlightenment?

Enlightenment as an inverted counterfeit of the Spiritual Path; the self-deification of human science.

There are many interpretations of the Enlightenment, few that convince entirely; in most there is at least some element of truth. The question, in other words, is poorly phrased—hence ultimately unanswerable. An alternative approach entails our examining the metaphor of enlightenment. The historical structure of this metaphor entails a shift akin to that from night to day; yet this shift has been realised by man, hence is perhaps felt as more akin to lighting a lamp. There are here echoes of Prometheus, though that tale is commonly interpreted as running contrary to the self-consciousness of Enlightenment thinkers. Here light is further taken as a metaphoric of truth, hence the retrospective vision of that prior as the ‘dark ages.’ Yet we may note that the progress thereafter took the path of a specific sort of enlightenment; one which has little in common with spiritual visions of this phenomenon.

Indeed, we might well think of the Enlightenment as an inverted counterfeit of spiritual enlightenment. Where the spiritual path is individual, for instance, the Enlightenment was claimed for humanity as a whole. The metaphysic implied may also be contrasted with that common to spiritual traditions; at which we find, again, an apparent inversion. The mystical core of most major traditions entails a central truth: that of wholeness, as much in Eckhart as in Sufi texts. Yet the difficulty here is that such a thing is difficult to express in language; in fact, it is fair to think it impossible. A word only holds such meanings as we bring to it, hence it would seem an experience of wholeness is necessary for such a thing to be understandable; and indeed, such is the content common to mystical experiences.

Nevertheless, we may try to gesture at some implications of such an understanding; at least to illustrate the concept by negation. The central truth of this mystical conception of wholeness is its apophatic character: it tells more about what is not than what is. Here we can compare this to the philosophical intuition of Bergson, as akin to Socrates' daemon; it is the voice that negates. Most obviously, we can see that this voice negates all that contradicts wholeness; that is, it denies absolute truth to fragments and objects. This must be understood to strike at the heart of idealism—as well as materialism, at least in its vulgar forms in which it is more a mundane idealism of the sensible world. The ideas which we posit in thought are held, on this mystical view, to have reality only insofar as they participate in the greater whole.

There is in Jain epistemology the idea that to understand a single object entirely would be to understand the universe as a whole. This is taken as the ideal of (epistemic) enlightenment in Jainism, a state acquired by only some few in their escaping conditioned existence; yet alongside this, of course, goes the whole stringent moral code and so on. This epistemology gives rise to the view of anekāntavāda, in which reality is understood as fundamentally many-sided; or literally, as characterised by non-one-sidedness. Such a doctrine stands against all declarations of absolute or exclusive truth. Where Greek logic, at least in the form we have inherited, entails an emphasis on whether, for the Jain it is instead a question of somehow. Greek logic is thus committed to the principle of non-contradiction; and indeed, it holds this as a fundamental and unavoidable tenet. Hegel disagreed with this, yet his view still can be seen to differ from that of Jainism.

For Hegel, all contradictions entailed an inner necessity which drove their inevitable resolution in a higher synthesis. This is not to disallowed contradictions but to accept their overcoming by the dialectic of thought. Such an admission is necessary, as the formal logic which it opposes fails to account for much of our experience.1 Hegel's linear dialectic of necessity can be seen as an effort to avoid the threat of dissolution which Aristotle had thought an inevitable result of renouncing the principle of non-contradiction. This metaphysical law implies a straightforward progress of dialectical assimilation until all is united in the Absolute Idea. Here we find, once again, an inverted counterfeit of enlightenment understood as the mystical perception of wholeness.

The notion for Hegel is that of a divine thought which, by the inevitable process of its dialectic, ultimately culminates in an essential unity. This is an idealistic monism which reconciles becoming as the dialectical unfolding of being as it assumes its final state. The whole here is contained in Spirit and the Absolute Idea as akin to the growth of seed into tree; and thereafter, its ultimate realisation in death. Yet this unity is of a very different kind to that of the mystical traditions; it is of reason as opposed to revelation. Hegel thought that such a thing could be grasped by a mind, forgetting that all objects are the same size; each is that we grasp, hence determined by the size of our hands. We cannot grasp wholeness in the same way as we might, say, an apple; it is an impossibility in the same way as I cannot grasp my car, the earth, etc. The problem is that my hands are too small: I am a finite being.

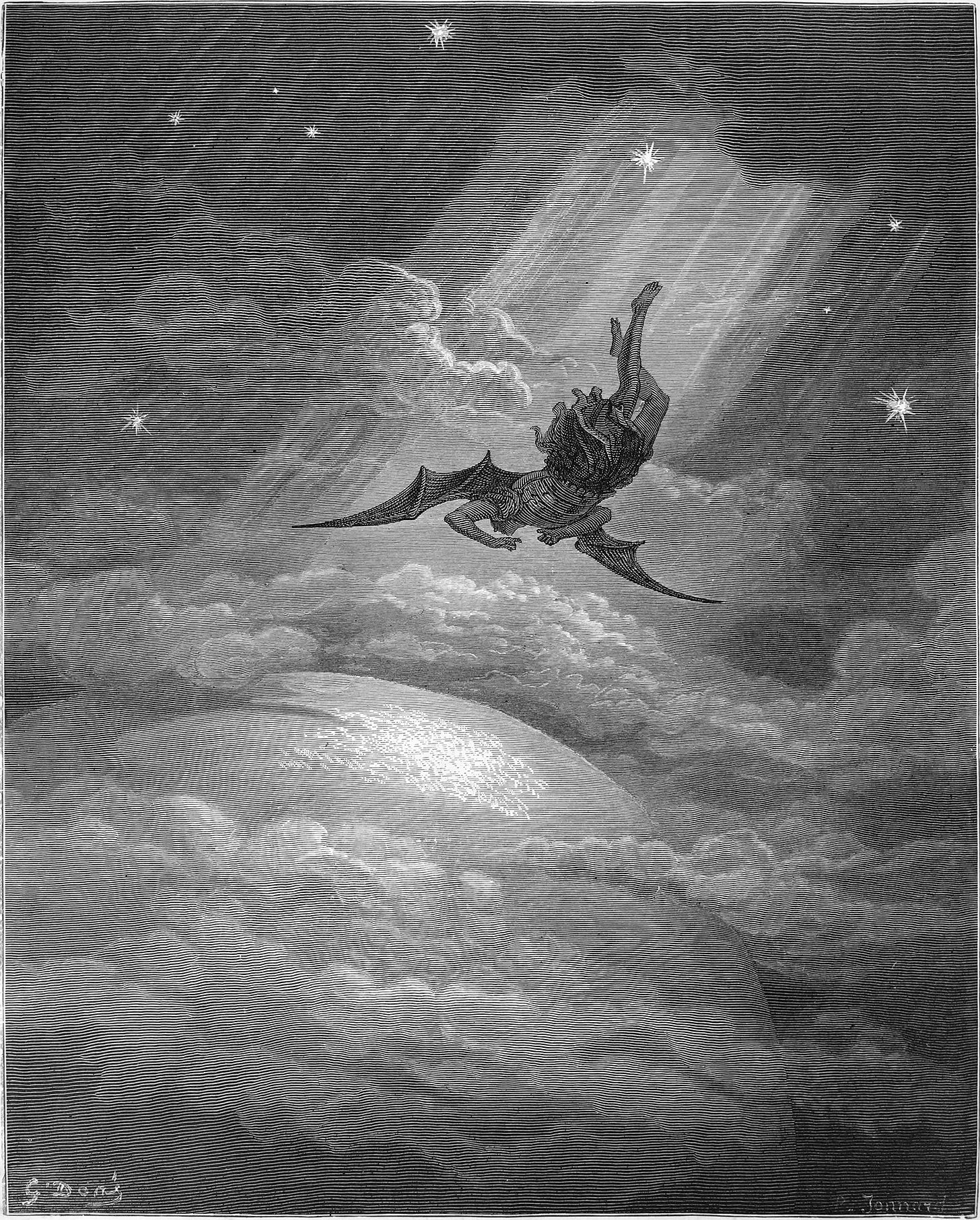

This is what Hegel forgot; and it seems, what the Enlightenment forgets also. We might read in Hegel the ultimate system of the Enlightenment ideal; it is, as Ilyenkov puts it, the self-deification of science—and in Hegel it found one capable of self-consciousness in this pursuit, that he thereby spoke its essential image. For in Hegel, we find the deification of human thought; not the thought of a human, not of a man or even men: of Man, as against God. This is the false light of the Enlightenment; whereby we are as Lucifer. Hubris is pursued eternally by Nemesis; that much is known. Much of the cost has already been paid, far more will surely follow; a rot is apparent in all our techniques, every solution comes costly as the monkey’s paw. We have dismantled the eternal order; replaced it with the temporal. Man has assumed the throne; if only temporarily. And all this out of pride, yes, but also as fulfilling our dharma—all is in preparation for the coming age.

Some may well double-down on ~formal logic, to those: “The lips of wisdom are closed, except to the ears of Understanding.”