The hand in human history

> For according to that which is present to them doth thought increase in men.

For as each man has a union of the much-wandering limbs,

So is mind present to men; for it is the same thing

Which the constitution of the limbs thinks,

Both in each and every man; for the full is thought.1

Anaxagoras claimed man is intelligent for having hands, while Nishida suggests that man has hands for his being intelligent.2 This second seems doubtful on the face of it, at least considered ontogenetically—for the child plainly does not sprout hands upon acquiring reason—but we may follow another angle for a more sympathetic account.

Take the closest creature having hands, trace their phylogenetic development through to the nearest ancestor which we would say did not have hands. See these have hands, and then this does not. This creature has—something, some stubs which end their arms at least. Likely they have some sort of hand-like composite, a branch of little limbs. What is the difference then, what is it that these are not hands?

The difference between humans and our closest primate relatives seems to be the range of motions of which our hands are capable, that there is a qualitative difference in terms of the capacities of the human hand. That one have an opposable thumb is taken to be the definition of a hand, but here there are more candidates than we might imagine. Revesz distinguishes these so-called thumbs by the fact they “cannot bring all the finger tips into contact with it because of its small size and low position”—for which reason, he continues, the thumb “loses much of its mobility and usefulness.”3

The specific distinction is that the human hand has a thumb positioned just so, that this allows the human hand to carefully and efficiently explore an object. For the lower apes, the size and positioning of their thumbs limits them to rolling an object if they wish to sense its aspects entire. The human thumb, in contrast, serves perfectly as a flexible scaffold for manual action. We are thereby able to execute all manner of dexterities: “to bring things into a desired position, to change them quickly and accurately, and to adapt oneself to the continuously varying pressure relationships.”

We might here compare the human hand to the grasp of soft-limbed creatures—of the octopus, for instance. The octopus conforms to the object grasped, and yet it does not maintain itself in the face of this; rather their form is assimilated to that of the object. This is in contrast to man, where the grasp manages a contradiction: assimilation and accommodation are here united in the human hand.4

This is the minimum of what it is to be a hand, qualities which are mirrored in human activity—including thought, really a subspecies of activity. The hand thus corresponds to all it renders possible, in which sense we are intelligent for having hands. Here also the contradiction in humanity: that for all our violence, we are the gentlest animal; that even our violence is unusually delicate, all the more so in its grandest forms.5

Yet we opened with the view that man may have hands for being intelligent; to which end we may see all this from a different angle. The hand is no mere appendage, rather the form of its activity is constitutive.6 This can be reflected and construed mentally as being—that is, as a static notion—but the hand exists foremost ever as becoming.7 The human hand is not the shape of an appendage, rather the form of this becoming.

The individual who is paralysed has hands, but they do not use them. They do not really have hands anymore, rather these hands merely belong to them. They are hands in no proper sense, are no longer animated by intelligence. As the contrary of a deaf-blind child we might imagine an individual born without hands, or either way without their use, and wonder about the paedagogy proper to such an individual.8

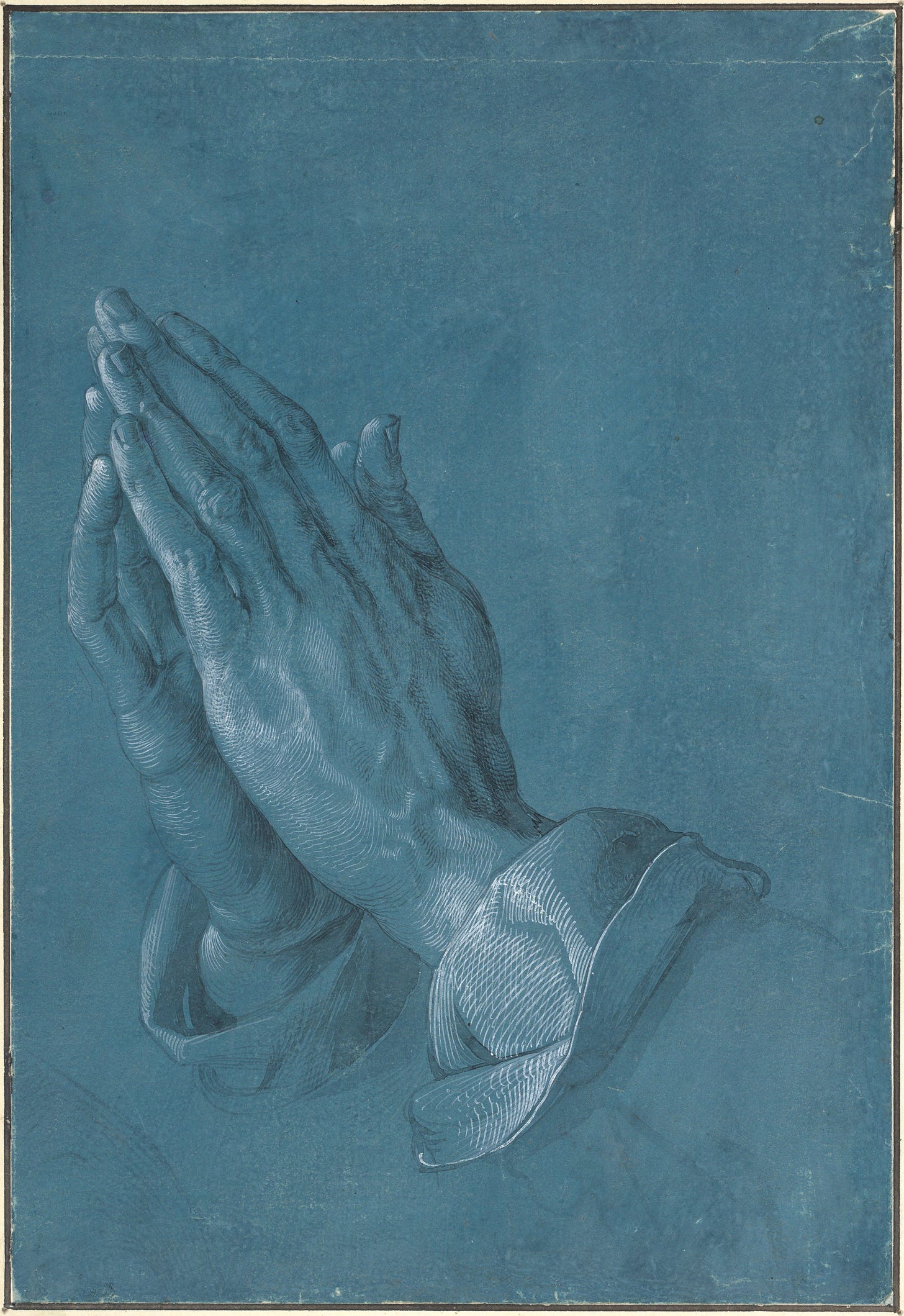

My sense is that this has been the problem for dolphins, that a lack of hands was their undoing; or perhaps their salvation, for Eve could not have picked that apple had she only had no hands. Were hands thus as Judas given by some dread necessity? And yet consider here the shape of prayer, whose form we have forgotten: “With hands held out as to touch or embrace a protector, to receive a gift, to ward off a blow, to present a helpless suppliant, unresisting or even offering his wrists for the cord.”9

Parmenides, Fragment 16.

Nishida, Place and Dialectic: “We cannot conceive of the human body as analogous to the biological body. It is not because they possess hands that human beings are rational. Instead it is because they are rational that they possess hands. What combines body and thing in this way is technē [gijutsu]. The human body must be technological [gijutsuteki].”

Revesz, The Human Hand: A Psychological Study.

The human hand, for instance, may measure in relation to its skeletal geometry; it thus retains a constant amidst change.

See the great warriors, Oppenheimer and Bethe.

Marx, Theses on Feuerbach: “But the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations.”

Marx, Afterword to the Second German Edition of Capital: “My dialectic method is not only different from the Hegelian, but is its direct opposite. To Hegel, the life process of the human brain, i.e., the process of thinking, which, under the name of ‘the Idea,’ he even transforms into an independent subject, is the demiurgos of the real world, and the real world is only the external, phenomenal form of ‘the Idea.’ With me, on the contrary, the ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought.”

Woe then to the doubly ailed, the deaf-blind child who has no hands!

Tylor, Researches into the Early History of Mankind.