The elephant as haptic form

> The order, the form, the texture of my books will perhaps some day constitute for the initiated a complete representation of it.

And they, saying: ‘Such is an elephant, such is not an elephant; such is not an elephant, such is an elephant,’ hit each other with their fists, and with that, monks, the King was pleased.

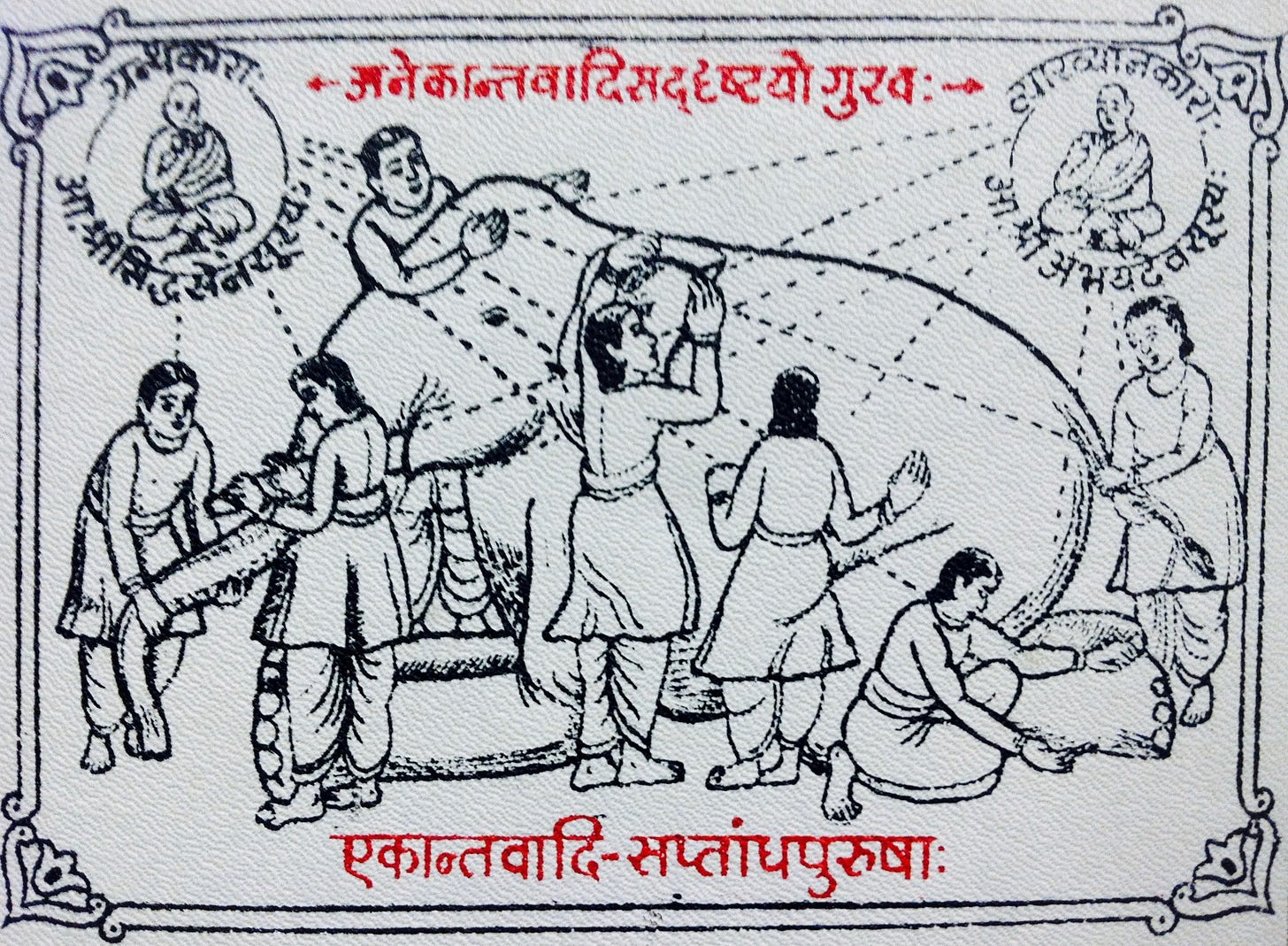

The point for the blind men is that they are forced to describe the elephant; it is this which causes their disagreement. From this perspective, the necessity of Jain logic is apparent: to say what the elephant is is inexpressible without some qualification. The ideal forms presented in the above image are represented by a visual metaphor for knowledge; it is this we must examine.

What is the relation which is here expressed? The idea seems to be that the individual integrates the totality of perspectives into a visual form; yet we might imagine also other sorts of forms. One such is the haptomorph, that we may know it by touch. This is the type of knowledge exemplified by the blind men; it is an important difference. Of course, we might read the idea as simply denigrating the sense of touch as one-dimensional—this needs to be examined.

Let us imagine instead we have been passed an unknown object; we are blindfolded. Here we take into hands a small item, call it a small plastic sculpture: something.

Touch gives rise to haptomorphic form; it is that image we acquire outside the visual.1 This arises within by our accomodating our hands to its form, thereby producing a negative of the object by the sense of proprioceptive presence/absence. This is a haptomorphic form: an embodied spatial knowledge derived from feedback between our activity and the impermeable processes in our environs; it is the chair acting on our behinds, it is the pen in our hands, it is the bare form of the thing-in-itself. This is the impermeability of things; it is that which resists, which is like but not us.

There are two basic ways to take a thing in hand—that is, there are two primary modes of manipulation. These are not categories but tendencies on a continuum; it is the location of our attention which differs between them. Attention can here be compared to a process, or more specifically, a flow: we flow into or through objects.2 The first is as an object and the second is as in-hand. The latter entails our containing the object and then holding or directing (or releasing) this integrated whole.

Here we are entirely new to the object, hence our attention is towards establishing sensory rapport with it. We roll it in our hands, in which apes and chimpanzees can do alike; yet the difference is that human thumbs are suited to more delicate haptic interactivity: our hands allow us also to feel the item with our fingers and thumb. If we fragment and examine this process, we find that it entails a movement in which features are identified based on position/negation—whereby we can never do more than crowd truth into a corner.

The question is, then: does this corner fill itself without a name? Returning to the blind men, each says a thing like-but-not it; or none of them are (exclusively) correct. They imagine the things which their aspect of the negative form renders salient: a pot, a store-house, a pillar, etc. These they say—and, somewhat inexplicably, it is to these they cling even unto throwing fists. This seems to have been a practical joke by the king, so perhaps he picked a particularly garrulous or argumentative group; it may simply have been a time of low public virtue, which may well explain also the king’s behaviour.

There is another option, one more easily open to our blindfolded selves, that we turn to the next aspect. We turn the object over; thereby see that it is many-sided. This is what anekantavada encourages us to do; and it always reminds us of the limits of our language. We cannot so much identify a thing as gesture to its features. Are we to say we less refer to something if we indicate its function as against its bare existence—is one somehow purer? No, all are certainly somehow it.

We may follow Parmenides, so far as reason goes, and hold that the All is somehow it; yet what does this mean for the fragments within—say, ourselves?3 Or in the same way, we may be within a house; what is our relation to the whole? These are best conceived on the basis of seeing language as gesture, whereby the view is that the elements of understanding are horizontally structured. There is no containment here but as metaphor. Reality is many-sided, at best we gesture to aspects.

The gesture is the inverse of haptic feedback; it is a negative image one removed; it refers to the negative image by excluding, as the finger pointed says as much what is not meant as what is. By this gesture is structured the play of our imagination, which depends on our knowledge and understanding; it also depends on our motivation, as in experiments in satisficing. We look and imagine what we think they mean; or when motivated, we make adjustments based on prior knowledge or by attending more closely.

Whatever the case, we cannot imagine what we cannot imagine. The supposedly free play of our imagination is thus structured twofold: as response to present stimuli and the sediment of past experience. These together generate a series of imagined possibilities; it is this confluence which determines the possibilities presented and the limits of our imagination in that instance. We may move around the elephant and gather together the pieces: pot, wall, pillar, etc. During this process, moreover, we may come to integrate these aspects into a single entity.4

These blind men, anyway—how did they lose their sight? We might imagine one had seen an elephant prior, perhaps they had touched it at the same time; then they might recognise it immediately. The visual image would be salient by virtue of its coherence with prior experience; in other words, our imagination depends on the sediment of experience and corresponds, so to speak, to an abstract topography in which the senses are integrated.5

But even then, what does this mean? The same question remains: does this corner fill itself without a name? Suppose we remember the thing, we have touched it before; but we do not know its name, even that we never knew. Then at best we may say that we recall having touched it before—and what does that mean? Then it depends on our prior experience, to what extent our further knowledge excludes salient possibilities; if the prior time we have made an exhaustive investigation and ended up without any notion, then we may at best say: “I have felt it before, and do now, but know no name.”

We cannot, of course, say: “I have felt it before, it is this.” This would be the equivalent of pointing, which was where we begun; hence the emptiness of our statement. What they asking want is a name; suppose then that we once knew it but have forgotten. Then we find within us the negative image of the name itself; that which corresponds exactly to the haptomorphic form; or rather, which corresponds to its exclusion of present possibilities—a trick mechanism which clicks open only at a particular name.

Might we not just make up a name? If the other doesn’t know, and if they think we do; then this may well work.6 This is perhaps how all words start, after all, in that poiesis consists in our acting as-if. My father has misled me before, and taking his word, I have acted as-if; it is impossible to say there was any fundamental difference between this and acting according to an actuality—that is, except for in the activity resulting and its consequences. There is not necessarily an objectivity to which all potentially refers in some supernatural sense; it is rather a matter of whether our acting as-if goes more or less smoothly. Mercifully most incongruence remains below salience.

Suppose instead the other knows the true name—and here not true in any Platonic sense, but true in the simpler sense of that which they expect.7 We might imagine this is a test. They have the authority to reward or punish us, hence we feel the pressure of this as an ought: we ought to give the proper name; it is not that we are unwilling, it is that we can’t. The name exists only as a negative image of itself, as the presence of an absence. I once had a test and thought of the word only the next morning when I was in the shower: stethoscope.

Why couldn’t I remember this name? No other name would fit; it was there and yet not; it was an abstract haptomorphic form, all that was missing was the name. This was not any absence as, say, the answer to a mathematical equation; it was not a matter of time or effort—it simply wasn’t there. There I was, hand on an elephant; its name trapped at the tip of my tongue.

For as each man has a union of the much-wandering limbs,

So is mind present to men; for it is the same thing

Which the constitution of the limbs thinks,

Both in each and every man; for the full is thought.8

Révész, The Human Hand: “Haptomorph form arises from resting touch, that is, when we touch the object without moving the tactile organ. We arrive at haptomorph impressions of a special kind in spontaneous movements of the limbs, when the organ of touch is excluded—walking, running, dancing, making gestures, etc. The true haptomorph forms appear only by joint operation of touch and movement. We produce such a haptic experience of form best when we finger small unknown works of plastic art after touching them unintentionally. In such a purely receptive touching, even in relation to a finely-modelled statue elaborated to the last detail, there emerges only a structurally differentiated schema of the body without attention to detail or proper articulation. Purely haptomorph shape is perceived when we exclude visualisation. This occurs rarely because visual images tend to appear directly and automatically thus disturbing the autonomous haptic experience of form.”

Continued: “In optomorph forms, impressions of touch, as a result of visualisation, are fused or blended with visual representations. The visualising of haptic impressions of form extends only to detailed successively touched parts of the object. Closer examination suggests that it is not the haptic form itself but the structure known through the sense of touch which becomes transferred to the sphere of vision.”

And finally: “The last and at the same time the most complex kind of haptic representation of form is the constructive one, that is, the form in which abstract factors operate beside intuitive ones. In this case, a more or less articulated and schematic image of form is supplemented by abstract influences, giving rise to a kind of integrated image.”

It is difficult to start a theory such as this, without assuming many things. Speaking of flow, for instance, something like this is here taken for granted—which is a case to be argued elsewhere.

This is a key common to spiritual paths: “The eye with which I see God, and the eye with which He sees me, are the same eye.”

This may remain an open question; it is only tangentially subject of our present inquiry. The question is the relation between unified percept and the name which we associate with it; whether the percept is unified by the name or ascribed on the basis of a prior unity. We may assume, for instance, that more general forms can contain a unity; as we might hold a figurine from a certain series but not know the character’s name; or we may grasp, at least, that it is a figurine. While concrete cases beyond this are difficult to imagine, we might think of an object which we can grasp and thereby is experienced as a unity; it is likely, however, that this is later applied metaphorically to the appearance of (imaginatively) separable unities; as we can identify aspects of an object, as the handle of a car, without removing them; or here they have some functional tone, thereby operate as a whole. I am inclined to think that the key is a salience which entails a certain action possibility; and that this is what ‘picks out’ the aspect, whether as the possibility for acting on or indicating.

Elephant skin is surely distinctive—if you’ve touched one, please tell me about it.

Here assume there is no third-party with which to check.

We will leave aside for now the crucial question of how such truth confronts us as something external; but more or less it is on this model, that it is held by some ought structure or such moral authority as common usage entails for the specific context. If we wish to use a word differently, as I may here, then we either assert this and hope to be taken seriously or we must argue our case. I am just hoping you play along—what’s the harm, anyhow?

Parmenides, Fragment 16.