Some monetary aspects of the Butlerian Jihad

Notes on value as an ordering principle.

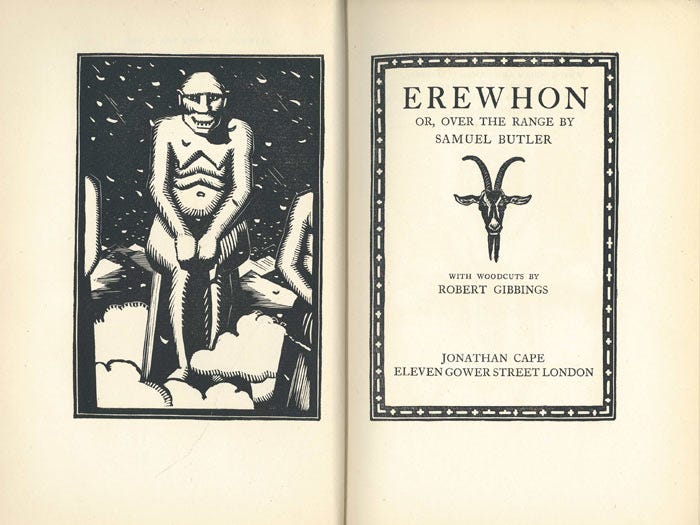

There is a crisis of value, of not knowing what’s worth what; and so it makes sense, since so much has been trash. Today the easiest answer is that of the market. Money and meaning are two contradictory modes of social ordering. This is among many insights, perhaps not all as strictly intended, of Samuel Butler; better known as author of the Butlerian Jihad. The world of Erewhon entails an alternate set of values, one reified in its musical banks; a second set of currency, more sublime than practical:

... this building was one that appealed to the imagination; it did more—it carried both imagination and judgement by storm. It was an epic in stone and marble, and so powerful was the effect it produced on me, that as I beheld it I was charmed and melted. I felt more conscious of the existence of a remote past. One knows of this always, but the knowledge is never so living as in the actual presence of some witness to the life of bygone ages. I felt how short a space of human life was the period of our own existence. I was more impressed with my own littleness, and much more inclinable to believe that the people whose sense of the fitness of things was equal to the upraising of so serene a handiwork, were hardly likely to be wrong in the conclusions they might come to upon any subject. My feeling certainly was that the currency of this bank must be the right one.

This building stands for tradition, that which entails an inherited order; as against this there is the market, an order of only walking men—that is, a temporal order. Here the ground is constantly shifting.1 Surely it is a rational system, one useful and which overall makes sense. This seems to be Butler’s view. The world of Erewhon is a mirror of our own, in which its author highlights by the strange salience of inversion. There the criminal is not punished, say, instead treated as ailing; yet the sickly suffer for their (supposed) sins. Where tuberculosis ends in court, perhaps to die in prison; the criminal class are instead sent to a straightener:

... a class of men trained in soul-craft, whom they call straighteners, as nearly as I can translate a word which literally means “one who bends back the crooked.” ... They send for the straightener at once whenever they have been guilty of anything seriously flagitious—often even if they think that they are on the point of committing it; and though his remedies are sometimes exceedingly painful, involving close confinement for weeks, and in some cases the most cruel physical tortures, I never heard of a reasonable Erewhonian refusing to do what his straightener told him, any more than of a reasonable Englishman refusing to undergo even the most frightful operation, if his doctors told him it was necessary.

Leaving aside the absurdity of this, and the (obvious) intent in its presentation, my interest is with the musical banks. There the money is worth nothing, none do any but pay their respects; then they withdraw and deposit, carry these practically worthless yet socially valuable notes. Butler here critiques religion, but in this highlights a metaphor for morality: that of a currency.

Take here art as an instance of the moral life, a leap perhaps but they play about the same: the artist is defined foremost by creative activity in which taste reflexively guides their behaviour. The same is so for a moral individual: to live is akin to a creative activity in which taste reflexively guides behaviour—as the painter dabs his canvas and assents, or we recoil at remembering some drunken antic. This is not primarily a matter of reason but taste; it is a subconscious sensation, something grasped more by gut than mind.

Butler makes this comparison explicit when his protagonist visits Erewhon's grand Colleges of Unreason:

... those who were studying painting were examined at frequent intervals in the prices which all the leading pictures of the last fifty or a hundred years had realised, and in the fluctuations in their values when (as often happened) they had been sold and resold three or four times. The artist, they contend, is a dealer in pictures, and it is as important for him to learn how to adapt his wares to the market, and to know approximately what kind of a picture will fetch how much, as it is for him to be able to paint the picture.

Something such as this can be seen in determining one’s life. There is freedom today, no doubt; yet we must of course be reasonable! Those that paint against the market will have little luck in life; far better to play the game, or so some say. Yet there is in this world also a musical bank, that from which even the starving artist receives his spirit’s stipend.

“Therefore whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock. And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.”