On thinking oneself and other things

"A man's at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with."

The central task of any true logic is not, as Hegel thought it, the unfolding of abstract knowledge—rather it is the unfolding of the concrete mind in its embodiment; it is concerned with neither ideas nor formal rules but the origin and operation of thought in itself. Here the appropriate method is to trace the dialectic of its ontogenesis; or more plainly, it is an evolutionary psychology. The single assumption therein is that all proceeds by exaptation—as required by the parsimony of nature, that life never exceeds itself unnecessarily.

Piaget has here done us an invaluable service, whatever the status of his specific theories, in adumbrating the broad shape of infant development. We can see from this, at least, the outline and rhythm of an unfolding mind; a process neither wholly inward nor outward:

Intelligence begins neither with knowledge of the self nor of things as such but with knowledge of their interaction, and it is by orienting itself simultaneously toward the two poles of that interaction that intelligence organises the world by organising itself.1

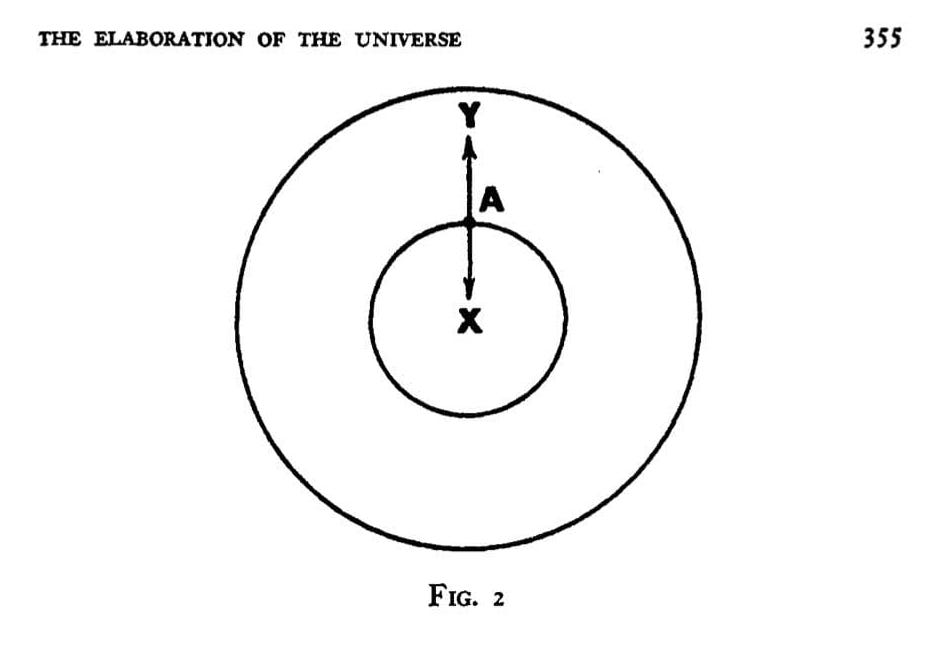

This is the meaning of any dialectic monism; it is an intelligent materialism. The world is taken at once (egocentrically) as characterised by embodied realism; and then (allocentrically) as foremost an undivided wholeness in flowing movement. Yet we thus project beings upon the face of Being—objects, things, concepts, ideas, etc. How do these come to be, wherever did we get such strange notions?

To begin we must see ourselves reflected in the eyes of another—like-but-not-me:

Man becomes an I through a You. What confronts us comes and vanishes, relational events take shape and scatter, and through these changes crystallises, more and more each time, the consciousness of the constant partner, the I-consciousness. To be sure, for a long time it appears only woven into the relation to a You, discernible as that which reaches for but is not a You; but it comes closer and closer to the bursting point until one day the bonds are broken and the I confronts its detached self for a moment like a You—and then it takes possession of itself and henceforth enters into relations in full consciousness.2

Yet, Buber continues, there is a further movement here:

... the maturing body as the carrier of its sensations and the executor of its drives stood out from its environment, but only in the next-to-each-other where one finds one’s way, not yet in the absolute separation of I and object. Now, however, the detached I is transformed—reduced from substantial fullness to the functional one-dimensionality of a subject that experiences and uses objects—and thus it approaches all the “It for itself,” overpowers it and joins with it to form the other basic word. The man who has acquired an I and says I-It assumes a position before things but does not confront them in the current of reciprocity. … In his contemplation he isolates them without any feeling for the exclusive or joins them without any world feeling. Only now he experiences things as aggregates of qualities. Qualities, to be sure, had remained in his memory after every encounter, as belonging to the remembered You; but only now do things seem to him to be constructed of their qualities. … Only now does he place things in a spatio-temporal-causal context; only now does each receive its places, its course, its measurability, its conditionality. ... This is part of the basic truth of the human world: only It can be put in order.3

This is man’s fall into This World, a watershed in cognitive development; it is the point at which become self-conscious of ourselves as a thing among others like-but-not-me. This is the birth of It; that is, of reality—in its root sense, as res, ‘relating to things.’4 Here we enter into the collective lifeworld which Hegel called Spirit, to which Plato gestured with his forms, that which was long treated as supernatural or inexplicable but has since become amenable to natural explanation:

Language belongs in its origins to the age of the most rudimentary form of psychology: we find ourselves in the midst of a rude fetishism when we call to mind the basic presuppositions of the metaphysics of language—which is to say, of reason. It is this which sees everywhere deed and doer; this which believes in will as cause in general; this which believes in the ‘ego,’ in the ego was being, in the ego as substance, and which projects its belief in the ego-substance on to all things—only thus does it create the concept ‘thing.’5

We find, in other words, an image of ourselves as Narcissus; that This World is but the ego writ large. The ‘ideal realm’ we find none other than ourselves refracted; no more than what we have put there—of this arises a caution: that one must seek behind mere things, to listen rather than dictate.6 And further, that there is thus nothing of actuality in thought or language, all is as a gesture; at best we may play pretend with mime or marionette:

All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts.

Piaget, The Construction of Reality in the Child.

Buber, I and Thou.

Ibid.

Of course, this does not mean that it is not useful or even good—only that all is necessarily in some sense a lie, that we ought be aware of this; hence Nietzsche speaks of ‘truth and lies a non-moral sense.’ For all must more or less lie if we are to say anything at all, as admits Quine: “We are prone to talk and think objects—for how else is there to talk?”

Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols.

Klages: “That which has been pierced by the searchlight of the intellect is instantaneously transformed into a mere thing, a quantifiable object for our thought that is henceforth only mechanically related to other objects. The paradoxical expression of a modern sage, ‘we perceive only that which is dead,’ is a lapidary formulation of a deep truth.”