McNamara and the Chinese room

> Forgive them Father, for they know not what they do.

We may consider a variation of an argument popularised by Searle, albeit here in quite different circumstances: the Chinese room argument.1 Here we imagine a room in which an individual resides, now this individual does not understand a word of Chinese. This is important because from time to time, slips of paper with Chinese characters are fed through a hole into the room. The individual has, however, a set of formulated programs which allow him to perform manipulations on the received characters and thereby return a modified set—at which, Searle argues, for the individual outside of the room then it would seem that someone fluent in Chinese was within. Of course, this was intended by Searle as argument for what might be called ‘artificial intelligence without understanding.’ Our intent here is quite different.

For Searle’s purpose, the content of these inscriptions is irrelevant. Suppose, however, that this process was endowed with a specific meaning. Those that sent through the slips were providing information, and the individual in the room was performing calculations on these, from which he thereby sent out orders. Suppose, for instance, that this process was used to devise improvements upon some aspect of, say, a boiler. If somehow there was a fault in the set of instructions used to perform this calculation, would we hold the individual morally responsible for the burns endured by those subject to an accident directly consequent from this flaw? Perhaps we would not—instead we might draw attention to, say, whoever provided the programs.

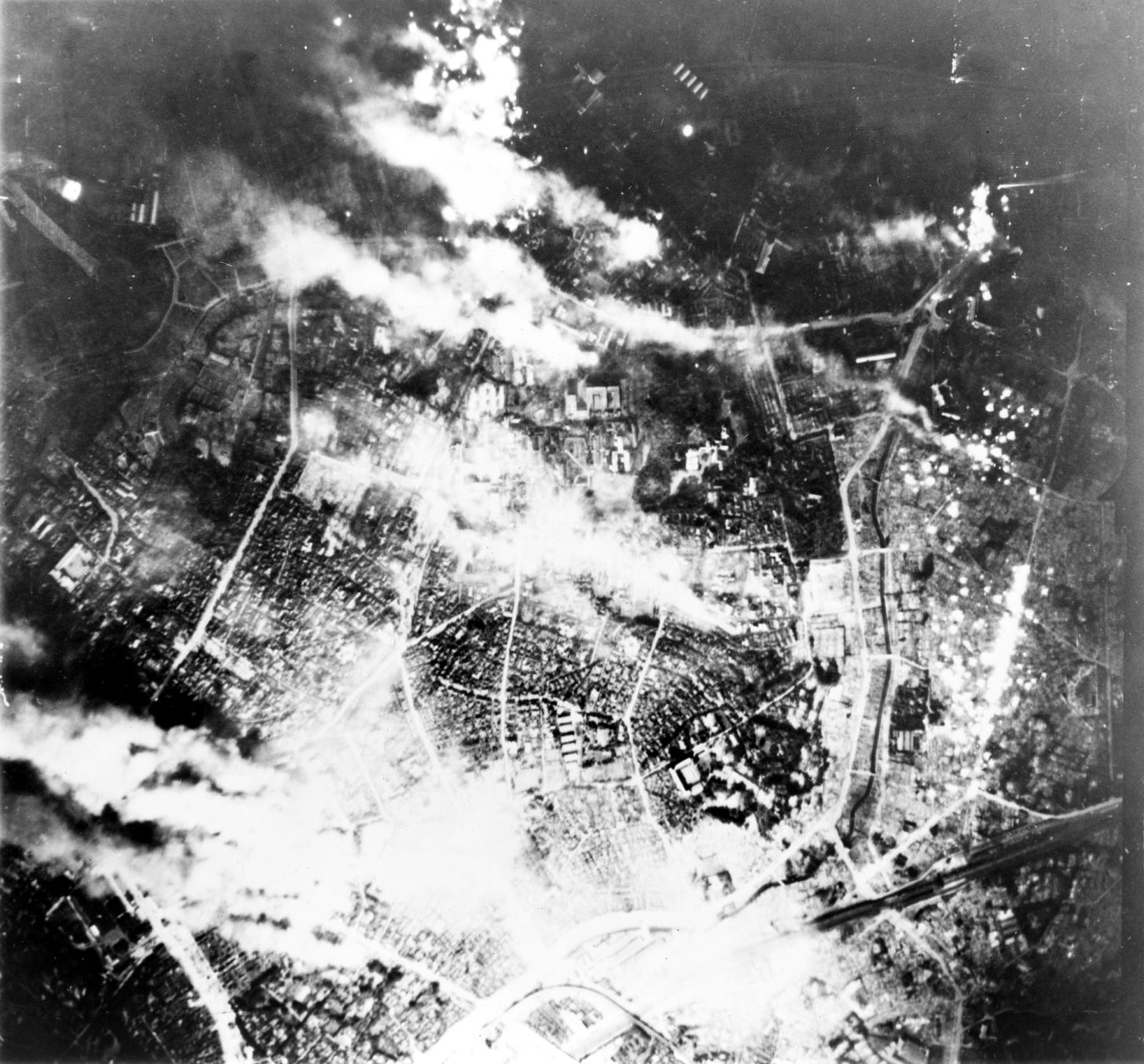

But take another example, instead of calculations for the boiler, the process involves calculations as to the efficiency of various uses of weaponry in a military scenario. Suppose, for instance, that the question put to the individual within the room concerned the efficiency of current bomber tactics. The results which the individual sends out indicate—entirely unbeknownst to them—the necessity of a sharp change in tactics; indeed, it suggests that the optimal use of these resources would be the large-scale use of incendiary munitions against a city inhabited largely by civilians.

Searle, 1980: “Suppose that I’m locked in a room and given a large batch of Chinese writing. Suppose furthermore (as is indeed the case) that I know no Chinese, either written or spoken, and that I’m not even confident that I could recognize Chinese writing as Chinese writing distinct from, say, Japanese writing or meaningless squiggles. To me, Chinese writing is just so many meaningless squiggles. Now suppose further that after this first batch of Chinese writing I am given a second batch of Chinese script together with a set of rules for correlating the second batch with the first batch. The rules are in English, and I understand these rules as well as any other native speaker of English. They enable me to correlate one set of formal symbols with another set of formal symbols, and all that ‘formal’ means here is that I can identify the symbols entirely by their shapes. Now suppose also that I am given a third batch of Chinese symbols together with some instructions, again in English, that enable me to correlate elements of this third batch with the first two batches, and these rules instruct me how to give back certain Chinese symbols with certain sorts of shapes in response to certain sorts of shapes given me in the third batch. Unknown to me, the people who are giving me all of these symbols call the first batch a ‘script,’ they call the second batch a ‘story,’ and they call the third batch ‘questions.’ Furthermore, they call the symbols I give them back in response to the third batch ‘answers to the questions,’ and the set of rules in English that they gave me, they call the ‘program.’ Now just to complicate the story a little, imagine that these people also give me stories in English, which I understand, and they then ask me questions in English about these stories, and I give them back answers in English. Suppose also that after a while I get so good at following the instructions for manipulating the Chinese symbols and the programmers get so good at writing the programs that from the external point of view—that is, from tile point of view of somebody outside the room in which I am locked—my answers to the questions are absolutely indistinguishable from those of native Chinese speakers. Nobody just looking at my answers can tell that I don’t speak a word of Chinese. Let us also suppose that my answers to the English questions are, as they no doubt would be, indistinguishable from those of other native English speakers, for the simple reason that I am a native English speaker. From the external point of view—from the point of view of someone reading my ‘answers’—the answers to the Chinese questions and the English questions are equally good. But in the Chinese case, unlike the English case, I produce the answers by manipulating uninterpreted formal symbols. As far as the Chinese is concerned, I simply behave like a computer; I perform computational operations on formally specified elements. For the purposes of the Chinese, I am simply an instantiation of the computer program.”