History is too large for men

Time was once a personal relationship with eternity, now tends instead entail a mathematical dominion over the individual.

Here I will deal in brief with the relationship between history and myth, and in this I will treat of issues of time in a like way as I once dealt with space. The basic principle of differentiation remains the same here as it was there: egocentric and allocentric, as presence and representation. This distinction is never absolute but rather reflects a whole swathe of historical processes, of which our understanding—and alike of those that went before us—is but the product.

The specifics of these processes must be dealt with further elsewhere, and here I intend to pursue treatment for space first, but we can see the same lines converging upon time in the overturning of myth and the emplacement instead of history—or rather of our eviction from myth, thus our placement now in history.

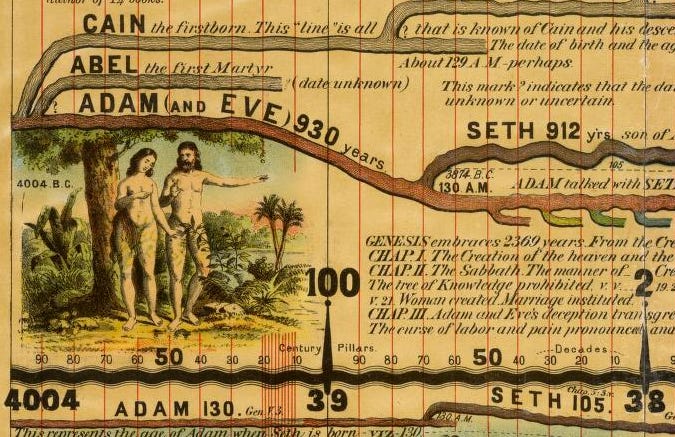

History is precisely that in which we must place ourselves, that its particular form is the chronological—from which we may trace its origins to the process of inscription that rendered as much first thinkable. History thus exists outside of any individual man, in which man is placed in relationship to a further arrangement of events. This is nigh definitional of the allocentric mode: that it is existence held at arm’s length, it is the relationship between objects in a space—a mode in which the objects foremost have meaning for one another rather than in any immediate relation to the individual.

We may here compare this to myth, in which the individual is placed immediate within a living time. The events of myth did not happen then or there, nor may we feel entirely comfortable calling them events; rather they are eternal and recur endlessly in the present. These are not distant events to be placed and analysed but rather shapes that echo throughout, and thus we see that they do not hold their place according to the dictates of any ordering or chronology; instead inhabit the whole.

Myth refers then to the living cosmos understood in its temporal aspect, and in this the comparison is akin to that between cosmography and cartography. Of course, the distant horizons remain yet within the realm of myth—and here we see how theology has retreated to these furthest reaches, likewise that even our cosmic cartography remains as yet only an aspiration; still it is this aspiration which is essential, that the realm of cartography and history aspires to achieving by brute force the totality which cosmography and myth once knew with ease. We were evicted from time and space, now seek construct anew; yet never more than a pale image of once living form.

This matters only because of its import in terms of men, of morals. History is now too large for men, is seen as something beyond mere individuals. The whole has been come to seen as the sum of men quantitatively considered, history as water boiling. Here the unity of units, an inverted counterfeit of its origin: that the unit is precisely that which is plural. This raises the individual only to subordinate them to the sum, in this sense Hegel was right; and in the sense of Marx, it is true.

These were not thinkers of men, they were thinkers of man. The sole solution cannot be found in either writer, only with the rise of existentialism does philosophy come to speak of the individual as such. Here the origin is plain, and in this a twofold choice: Kierkegaard or Nietzsche, Christ or Antichrist—I tell you, both answers are the same. They are in such absolute contradiction that they align entirely, in each we are asked to return to ourselves; a spiritual materialism, that the only way out is through.

See Kierkegaard against Hegel, see Nietzsche on the history of an error; each of these point us to a new relationship with time. Kierkegaard presents the Hegelian form of a dialectic, Nietzsche is more organic—in either case we have the same, Abraham and Übermensch. Nietzsche’s tightrope is continuous, Kierkegaard presents a jagged dialectic: aesthetic, ethical, religious. This is a basically Hegelian form: the individual is negated by their integration into culture, and yet it is only this assimilation which provides the basis for ethical action; that is, the individual can only be through society.

This is apparent in language, that the poet must absorb the form of spiritual culture before he can work creatively at its edges. The importance of poets in all their forms—for poiesis is the operant principle in all true confrontations with life, whether mother or poet, scientist or priest—is precisely that they contribute actively to history. They alone are the source of fresh water for the whole, without which time grows stagnant.

"The importance of poets in all their forms—for poiesis is the operant principle in all true confrontations with life, whether mother or poet, scientist or priest—is precisely that they contribute actively to history. They alone are the source of fresh water for the whole, without which time grows stagnant."

Thanks, I've been wondering why I bother, but there's no alternative.