Cosmos as presence and representation

"For existence has its own order and that no man’s mind can compass, that mind itself being but a fact among others."

The cosmos was once entirely present; now it is more often represented—what does this distinction entail? It can be illustrated by the contrast between time and timing; space and place. There is nowhere here any clear line, yet we can readily speak of a polarity; it is this which underlies the observed differences in space and time alike. This can be thought of as a shift from egocentric to allocentric; and further, from qualitative to quantitative; and in this adjustment of emphasis we see the central ordering principle characteristic of modernity. Here we will consider space and place.1

We are always in a place, but where is space? Kant said we could think of space free from things but not things free of space. By this he held that spatiality inhered not in objects but was of the mind. This is half-true, as all things: our embodied activity derives from our experience of the relations between objects (foremost as subject–object dyad); it is through an evolutionary and developmental history of such activity that we have acquired the internalised sense to which Kant appeals. When it comes to our immediate experience of space, however, we never encounter space without things nor things without space. These are interwoven in the actuality of concrete experience—indeed, we find all things are, as also time; it is the limitations of language that compel our pretending them separable.

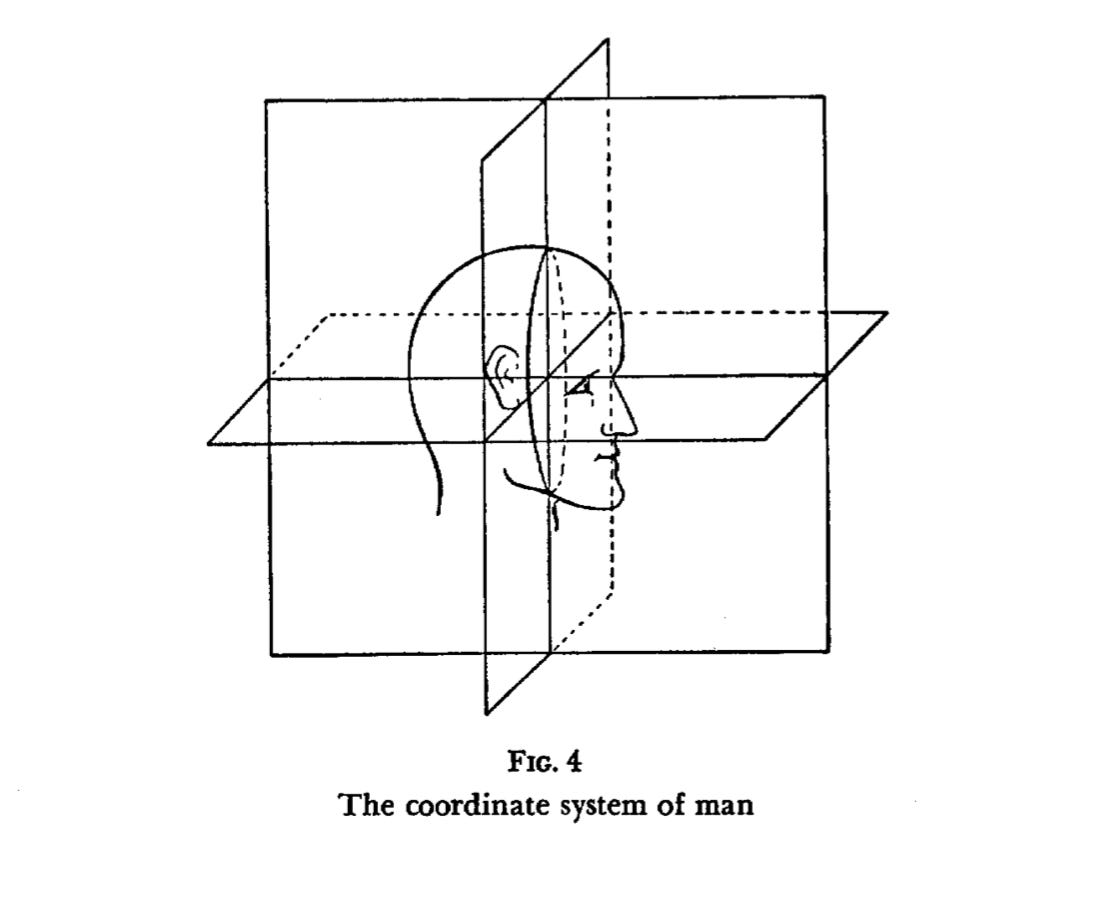

Egocentric space corresponds to embodiment, which can be understood as a sort of integrated biotechnics; at once embedded and imagined as orientational sense.2 We have something akin to a spirit level, by which tripartite structure we orientate ourselves in operational space: up–down, left–right, front–back. We may note here that time also carries a second-order orientation as mapped from the more basic spatial domain, as English tends to understand it as moving from front to back; some cultures have it instead moving from up to down; some have it from back to front; etc. All this depends essentially on the basic dimensional structure of space. Indeed, we find the same dimensionality present also in allocentric space.

Allocentric space differs foremost in the locus which operates as its ordering principle rather than the structure of the operation itself. The difference is that, as the name suggests, the centre has been displaced from embodiment; it is this movement which depends upon our capacity for representation. In this way we mirror egocentric space as an abstract intermediary. This can be seen to depend on our first conceiving of ourself as an object among objects; at which self-consciousness then leads, via ontological metaphor, to the positing of an objective world of things. This is the world of allocentric space.

This is exemplifed by the comparison of the certainities found in egocentric and allocentric space. The certainty of egocentric space is to be found in the familiar path; that of allocentric space, as (necessarily) represented on an accurate map. Of course, the accuracy of the map—as Borges makes so clear—is relative to the functional tone we take towards it. We must for this example take a map as used in embodied activity as our standard; it is this purpose which renders salient the measure of its certainty. Of course, the true measure of its certainty is twofold: first, that we act as-if (in most cases, we do not doubt our maps without some salient reason); and second, that it goes according to plan.

We may find in either case that the map and familiar path take us to where we want to go. Suppose it was at night, however, and the familiar path would be obvious superior. The map is limited in precisely that way which Borges’ story shows to be a necessity: it is designed for a purpose in mind, one which assumes certain conditions.3 This means daylight or some artificial light source, so that the map may be compared to the environment so as to find our way. Here we are reminded of an obvious fact: the map is not self-executing, it requires we imaginatively interpret it. This principle is true across the board and exemplifies a limit of representation: it tends to require conscious engagement.

This makes sense, of course, as the map is not meant to supplant our practical knowledge but rather to extend it. The map is the tool of someone that doesn't know their way around; it is a tool which suggests unfamiliarity, anonymity, complexity, etc. This is an abstract tool for abstract men, which is what we become amidst the marvels of modern transportation and organisation; it is a tool of the ignorant, whether within complexity (as a city) or at a distance (as in travel). If we knew the way, we would hardly use a map; what would be the point? The idea would never even occur to us: I leave home and then, next I know, I’m where I wanted to be.

The familiar path, in contrast, is a far simpler affair; yet it has its limits in that it requires, of course, that we first familiarise ourselves. This type of certainty is that which arises only in performance, as the first certainty (that of belief) is only relevant for our will to act upon something posited. There is no such distance in the immediacy of the familiar path; it shrinks to a point, is thereby entailed in its destination taken as an end of action. Here consciousness necessarily arises only to the extent that we are caused doubt or the process encounters some impossibility of continued progress down that route; we come to a landslide, for instance, which forces us to take a detour. When encountering such an obstacle we may cycle through several possibilities before assenting to one; it depends largely on our temperament.

If we do not know another way, then perhaps we will want a map. We may infer a possibility from our knowledge of the area surrounding the familiar path, in which we will be acting akin to as with a map: for it is an idea that the map represents as its referent, and the same is so for that we merely imagine to be so on the basis of our knowledge. The difference is between process and act; in one, the familiar path, it is a matter of flowing movement; in the other, it is a sequential series of acts—taken as a point, by which the imaginative interpretation produces a possibility which punctures the underlying process.4

The difference between imagination and a map is that in the latter an outline of the ideal form is concretely embedded as materiality. This is the difference between the free and structured play of the imagination. The imagination is always more or less structured, insofar as consciousness requires it take this form; yet what we here specifically term the structured play of the imagination differs in that the source of this structuring operates at a further degree of abstraction; it is ‘spooky action at a distance.’ This is the precise importance of the map as form; it allows us access to information beyond the singular soap bubble in which we ordinarily reside; it entails communication.5

The map works by its abstraction; it is represented via being translated and embedded in materiality, thereafter requiring an imaginative interpretation to come to life. Abstraction varies here, as one might between a map that shows a theme-park and the precise latitude and longitude of the same; it is the latter which lays the strongest claim to ‘objectivity.’ This is so because a thing is objective precisely to the extent that it is abstract; it is that which seeks to attain to the universally necessary, which it does by seeking to exclude particularity. We can see this in, for instance, the walking time provided by an app as compared to the slowed movement of an elderly man. He may find it takes him far longer than that prescribed, must learn to calculate himself in relation to the norm.

This is a world in which none live, rather it is one within which we think; it is a mediated Umwelt in which are indirectly contained—at best we may hope to fit. This mode of ordering lies behind the capitalist enterprise, industrialism, and rationalism as a whole. Whether the claims of rationalists are true in any higher sense is irrelevant, that they have proved effective is certain; though the same might well be said of looting. Irrespective, the success of this—which we call ‘progress’—can be seen directly in the birth of cities and the complexity of the world as a whole; it is this which further necessitates our conscious interaction, as when we read the manual for a newly purchased appliance. Children are taught early, as IKEA is just LEGO for adults. These days the world is more and more constructed in this way.

This is a fundamental aspect of what Jacques Ellul calls Technique—meaning not simply the individual operations but the totality as technical phenomenon, understood as an egregoric entity akin to Capital or Spirit. We may further clarify a distinction between embodied and extended technics; the former included both biotechnics and that which we have assimilated at-hand. The latter is that with which interact as an intermediary, as in Stiegler’s tertiary retention (e.g., an instruction manual); or as we interact more directly via an imagined ideality in which the object is taken as the immediate target of interpretation. Each entails our assuming the same attitude towards the object of our activity, in which we are at a distance from it; and this includes relating to ourselves, as when a psychotherapist (or app) has us treat our thoughts as scripts to be rewritten. We do not so much act as act upon ourselves; in the same way, we do not act but act upon the lines prescribed by technical means.

These abstract technics extend to medical treatments, especially medication; little wonder, then, that pharmaceutical companies are so powerful. We have made them powerful by our desired for mediated immediacy. The pill is perhaps the perfect metaphor for our society, so it is hardly surprising to find it sold expressly by the arch-technician of ‘dissident’ politics: the clear-pill. And this is the same everywhere, in which information is taken as equivalent to a political medication. Such is nothing but ideology. The true locus of politics is not the allocentric world of things; it is the immediacy of embodied existence—that is, it is not political at all; it is moral. We cannot take a pill to make us a better person. The culture war doesn’t matter; as a wise man once said on returning from battle: it is time to return to the greater war.

This inquiry can be separated from time only in abstraction, and nowhere is time here excluded in any positive sense; it is simply that the emphasis will be on space with time left implicit.

Uexküll, A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: “By holding one’s hand vertically, at right angles to the forehead, and moving it right and left with eyes closed, the boundary between the two becomes obvious. It coincides approximately with the median plane of the body. By holding one’s hand horizontally and moving it up and down in front of the face, the boundary between above and below can easily be ascertained. For most people, this boundary is at eye level, though many people locate it at the height of the upper lip. The boundary between in front and behind shows the greatest variation. It is found by holding up one’s hand palm forward and moving it back and forth at the side of the head. Many people indicate this plane near the ear opening, others indicate the zygomatic arch as the border plane, and by some it is even placed in front of the tip of the nose.”

Borges, On Exactitude in Science: “In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.”

We may see as a related case, the relations entailed in printed text and television; each operates at a distance, yet it is that the text requires imaginative interpretation whereas television carries the actuality of process. Of course, this is perhaps more a matter of degree than kind, as books can pull us through and television can give us pause or otherwise puzzle us—the point still stands.

Communications is that technics which deals with ideal action at a distance. This the difference between shooting someone and firing a warning shot at their feet; only the latter is communication, or at least of the sort with which we are immediately concerned—the other line, while interesting, must be left aside for now. This example demonstrates, either way, that communication entails the bringing forth at a distance of some phenomena which acts as a cue for the individual concerned.