China's century of humiliation and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race

This World was built by addicts and slaves.

China was responsible for what Francis Bacon thought the three great inventions: the navigational compass, gunpowder and its military use, and movable type for printing. Yet these three inventions were, of course, ultimately taken to their utmost not there but in the West. We cannot mistake the fact, moreover, that without these modernity would have been impossible.1 The development of firearms, for instance, can be directly tied to the industrial revolution, for it was this which created demand necessitating the use of charcoal; it was this which led to the use of coal, though only once England had burned most all its trees.2 This use of coal—and later, other fossil fuels—thereby enabled the nations of Europe to exceed the energy limits set by the annual solar economy; moreover, this process drove itself on by contagion in its effect on the European balance of power. In this way, therefore, was engendered that process by which a great machine could be seen to start in the West, and one which by its very success has since displaced all organic contenders.

Yet China contributed a further necessary element to the machine that would produce this revolution: namely, addiction. From the very beginning, the process has been driven by desires such as these; it is thus that De Vries speaks of a necessary prior in the ‘industrious revolution’ of Europe—in which workers were tempted by mass-produced luxuries into making a more rational use of their time so as to provide the necessary manpower for increasing industrial production. This was rendered explicit, as well as the linkage between such behaviour and money as a means of exchange, in the case of French colonialism in Madagascar:

The colonial government were also quite explicit (at least in their own internal policy documents), about the need to make sure that peasants had at least some money of their own left over, and to ensure that they became accustomed to the minor luxuries— parasols, lipsticks, cookies—available at the Chinese shops. It was crucial that they develop new tastes, habits, and expectations; that they lay the foundations of a consumer demand that would endure long after the conquerors had left, and keep Madagascar forever tied to France.

The aim, in short, was a situation whereby the people are “forced to labour now because they are slaves to their own wants.” Of course, in this Madagascan case, the Chinese ran the shops; so what was the necessity which they provided? The theory is similar enough; but this was not something provided willingly, or at least not in the same sense. The answer is opium.

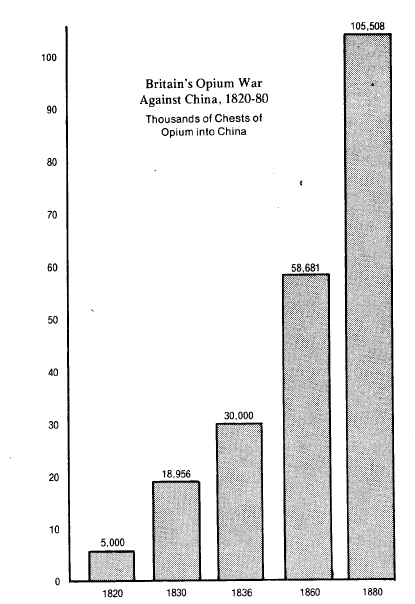

Opium was the final stage in the demand cycle for British-financed and slave-produced cotton. British firms brought cotton to Liverpool. From there, it was spun and worked up into cloth in mills in the north of England, employing unskilled child and female labor at extremely low wages. The finished cotton goods were then exported to India, in a process that destroyed the existing cloth industry, causing widespread privation. India paid for its imported cloth (and railway cars to carry the cloth, and other British goods) with the proceeds of Bengali opium exports to China. Without the “final demand” of Chinese opium sales, the entire world structure of British trade would have collapsed.

This unholy cycle of slavery and addiction constituted the engine by which the West won the world; it is perhaps no wonder, then, that the industrial revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race—a vast beast born of sin, bound only by Mammon.

Addendum on modern China

China did not modernise when it might have; instead was pillaged and pushed aside, hence the century of humiliation. Yet now some think her time has come again, as many have come to see in China an alternative to the failing political and economic structures of the West. This has led to, for instance, the positing of a ‘Beijing consensus’—as against the long-reigning Washington consensus—in terms of the pathway for developing nations. Many such nations, while wary of foreign influence, see in China an alternative example of developmental success. I am not so interested in this.

My interest is instead in those that see in China a model for the future of modernity, taking a state of relative development as a given. There are several ideas here, two of which can quickly be dealt with first. This is the notion that China is better governed than, for instance, the United States; and that seems almost certainly true, at least in some sense. The United States is rotting quickly; its stench becomes harder to deny with each twist and turn. Those that push for this position see the apparent authoritarianism of Chinese politics as a necessity for such capable government, that this is a trade others ought also make. Against this, there are those that see China as a threat to democracy worldwide. They also acknowledge China’s apparent successes, yet the tonality is reversed: from triumphant to tragic, a threat to the world. Neither of these is particularly interesting or important, only time can tell.

The key idea, however, is that which sees in China’s failure to modernise a possible immunity or resistance to the damage which modernisation has wrought in the West. There is the suggestion, and this seems broadly correct, that China's failure to modernise was partly a matter of social morality and philosophical ideals. This idea contains much well worth exploring, as has been done admirably by Yuk Hui. We can readily note, for instance, that the ‘spirit of capitalism’ directly entails a disrespect for customary modes of production; and moreover, a population willing to be uprooted. The wave which swept through Europe was successful partly in its strength, yet also necessarily in the weakness of all which might have otherwise opposed it.

Nevertheless, we must accept as a central fact that, whatever these limits were, China has since embraced the Western technical alternative with open arms—and they can hardly be blamed after a century of humiliation, with early slogans openly avowing the intent to learn from the West only so as to ultimately overcome them. This progress of opening perhaps began in earnest with the influx of Marxism, then under Deng Xiaoping was brought to all new levels. Whatever the considered philosophies and moral ideals of ancient China, today they are largely similar in terms of technical activity; such cultural ideals are but empty forms unless also underpinned in actuality by material activity and relations.

There thus remain many questions as to this sense of Chinese exceptionalism with regard to technics. An initial line points to the need for further consideration of her classical philosophies and the lines of descent into modernity; and moreover, that these be situated by comparative study in line with that of the West. The second is whether the apparently technical mode of Chinese political and economic activity does, in fact, differ in any fundamental way from that of the West. I take it as a working hypothesis that it doesn't matter what you say, what matters is how you act. China may well use its intellectual history to cultivate a new national myth; yet the question remains whether a technocracy with Chinese characteristics is really any different at all.3

Perhaps for this they deserve some blame, though such apportioning is generally useless; and more, that it was the West which used them and thereby dragged all into the race—a heavier proportion weighs here, to be sure.

I suspect that this is why the English are often so ugly today; a curse of the tree-spirits.

A further possibility remains, that which Yuk Hui suggests: a moral-metaphysical reconciliation of technics and heaven; yet a question here is whether, taking a materialist perspective, such a thing is even possible. This would need to be demonstrated to somehow result in a fundamental difference in the actual mode of technical activity—something which is hardly understood as it is, with most analyses failing to ‘touch the ground.’