Birth and behaviour in the sacred beetle

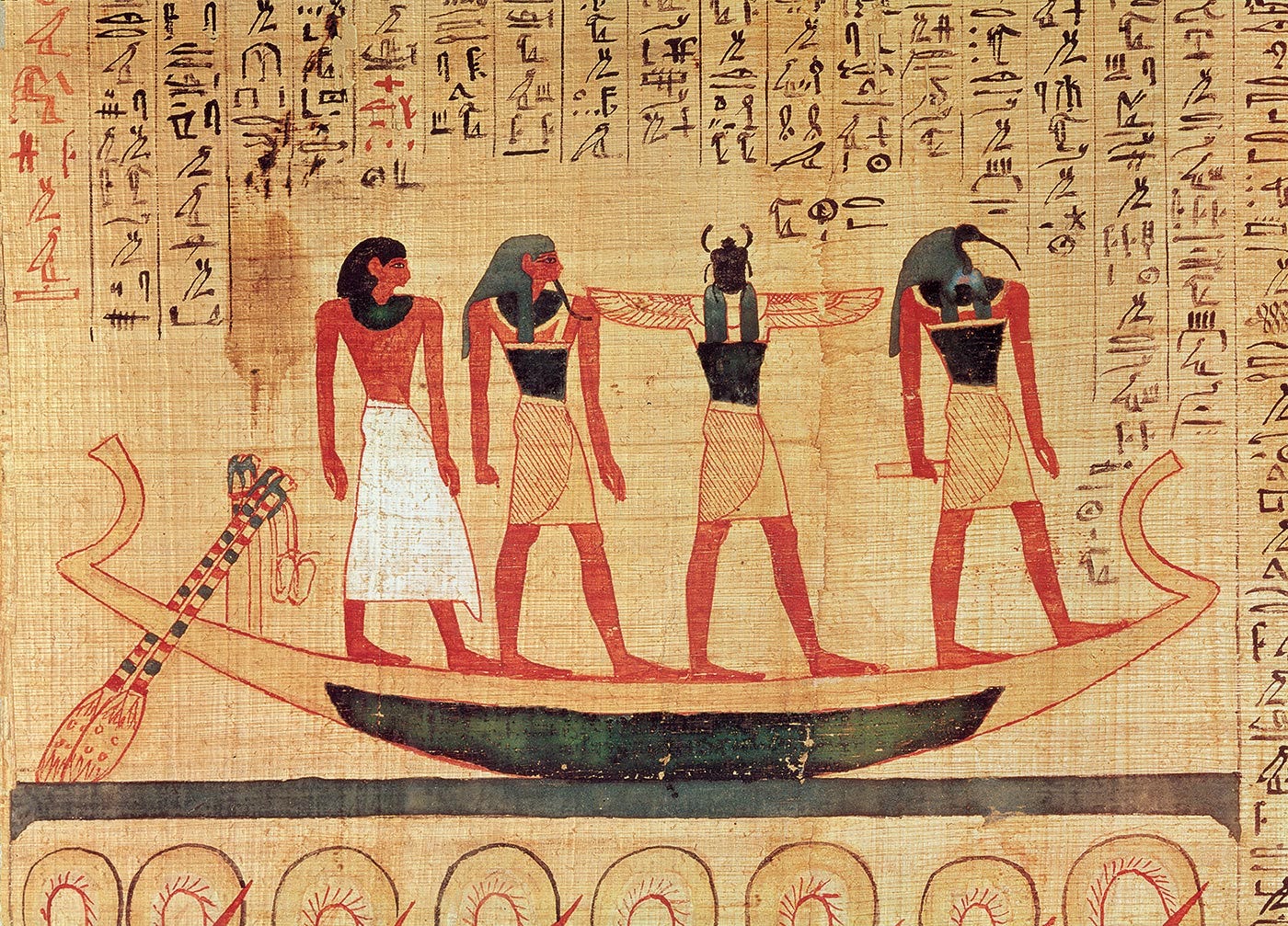

> Hail to thee, O Khepri, who came into existence by himself.

The early Egyptians fancied that this ball was a symbol of the earth, and that all the Scarab’s actions were prompted by the movements of the heavenly bodies. So much knowledge of astronomy in a Beetle seemed to them almost divine, and that is why he is called the Sacred Beetle. They also thought that the ball he rolled on the ground contained the egg, and that the young Beetle came out of it.1

We know now that the second claim is false while, strange as it sounds, the first is partly true. The ball itself is merely their store of food, the female is elsewhere making her own structure—a form more closely resembling a pear than a sphere. This sadly defies the Egyptian belief that there were only male beetles, a fact further lodged as support in their mythology of Khepri, the self-created scarab deity; the sun created all things, that the sun created itself.2 Here we may even see the faint threads which led ultimately to the theology of Akhenaten—but that is not our purpose now.

That the beetle is in fact a marionette of the heavens, however—this much is true. The beetle climbs upon their ball and there performs a ritual dance, in this process orient themselves. By these celestial signs they navigate in straight lines upon clear nights; a skill they lose only when conditions are overcast.3 We might wonder how this could have been known so long ago, may well seek dislodge this uncomfortable fact as mere chance; it seems strange, after all, that they could ascertain such a subtle sign and yet not notice the female form, nor that eggs were placed not within the spherical ball but the pear-shaped production of the female.

The beetle is born in this pear-shaped structure, they then eat their way through this storehouse carefully at first and grow by stages to become the form we know—along the way traversing various unfamiliar shapes and states. And when they at last break free of the structure in which they have developed, we may note Fabre’s observation:

At first he shows no interest in food. What he wants above all is the joy of the light. He sets himself in the sun, and there, motionless, basks in the warmth. … Presently, however, he wishes to eat. With no one to teach him, he sets to work, exactly like his elders, to make himself a ball of food. He digs his burrow and stores it with provisions. Without ever learning it, he knows his trade to perfection.

We may marvel here that this little beetle, having prior known only the darkness of his pear-shaped accommodation, comes into this world a consummate craftsman.4 They pause a moment to give thanks and then shortly begin their careful work. The source of this is yet unknown, alone we know that they did not learn it like men from one another. Somehow it is a knowledge embedded in the individual at birth; that it might well have been put there by the stars.5

Where once the solely male beetles were considered signs of Khepri, then, where once Khepri was considered through this sign, now we have the mundane facts of science.6 Yet this negation is only apparent, for we find in the beetle a return to its origin: like Khepri, who created himself from nothing, the beetle too carries itself within itself; an intrinsic knowledge of its nature, a blueprint for behaviour born of the cosmic void.7

Fabre, Souvenirs entomologiques.

Goff, Symbols of Ancient Egypt in the Late Period: “The Egyptian word for ‘scarab’ is hpr (Kheper or Khepri), which signifies ‘come into existence,’ ‘arise,’ or ‘happen.’ In its plural form it signifies ‘manifestations,’ ‘forms,’ or ‘stages of growth.’ Its implications are complex.”

Dacke et al. (2013), Dung Beetles Use the Milky Way for Orientation: “African ball-rolling dung beetles exploit the sun, the moon, and the celestial polarization pattern to move along straight paths, away from the intense competition at the dung pile. Even on clear moonless nights, many beetles still manage to orientate along straight paths. … we show that dung beetles transport their dung balls along straight paths under a starlit sky but lose this ability under overcast conditions. In a planetarium, the beetles orientate equally well when rolling under a full starlit sky as when only the Milky Way is present.”

And more, it seems, an astronomer of sorts.

Here the concept of ‘motor babbling’ comes to mind, which in human infants refers to the stage of in utero learning where this apparently aimless behaviour contributes to early somatic mapping. They learn there not only the sound of their mothers voice, the echoes of the world, but also the shape of their own form, the angles of their joints and simple aspects of motor control. This idea has not left me ever since I first heard of it when reading about cognitive developmental robotics in a little town below Mumbai; it babbles restlessly in the back of my mind, waiting someday to be born. The idea, then, is that we ought look at the beetle’s behaviour in the darkness prior to emerging from their creche.

I think here unwillingly of Dawkins, and the epigraph of Legg’s dissertation: “Mystics exult in mystery and want it to stay mysterious. Scientists exult in mystery for a different reason: it gives them something to do.” This is a proper place to return, for I cannot but be of my age; even here my interest in the sacred beetle is guided by concerns little different from Legg, that I wish to know the meaning of these phenomena for the pursuit of things.

The term ‘cosmic void’ is here important; it is a contradiction in terms. Etymologically its meaning refers us to the emptiness of an orderly universe. These things beyond thought come from this empty universe. We can consider the whole in nested dichotomies: being and nothingness as cosmosphere, land and sea as geosphere, life and death as biosphere, order and chaos as noosphere. These all arise at the point of their own contradiction, else cease to exist; it is the whole below thought which sustains all this.

We must worship the Formless by means of form.