A brief history of the Encyclopedia

Yggdrasil was pulped that the Phenomenology of Spirit might be printed upon it.

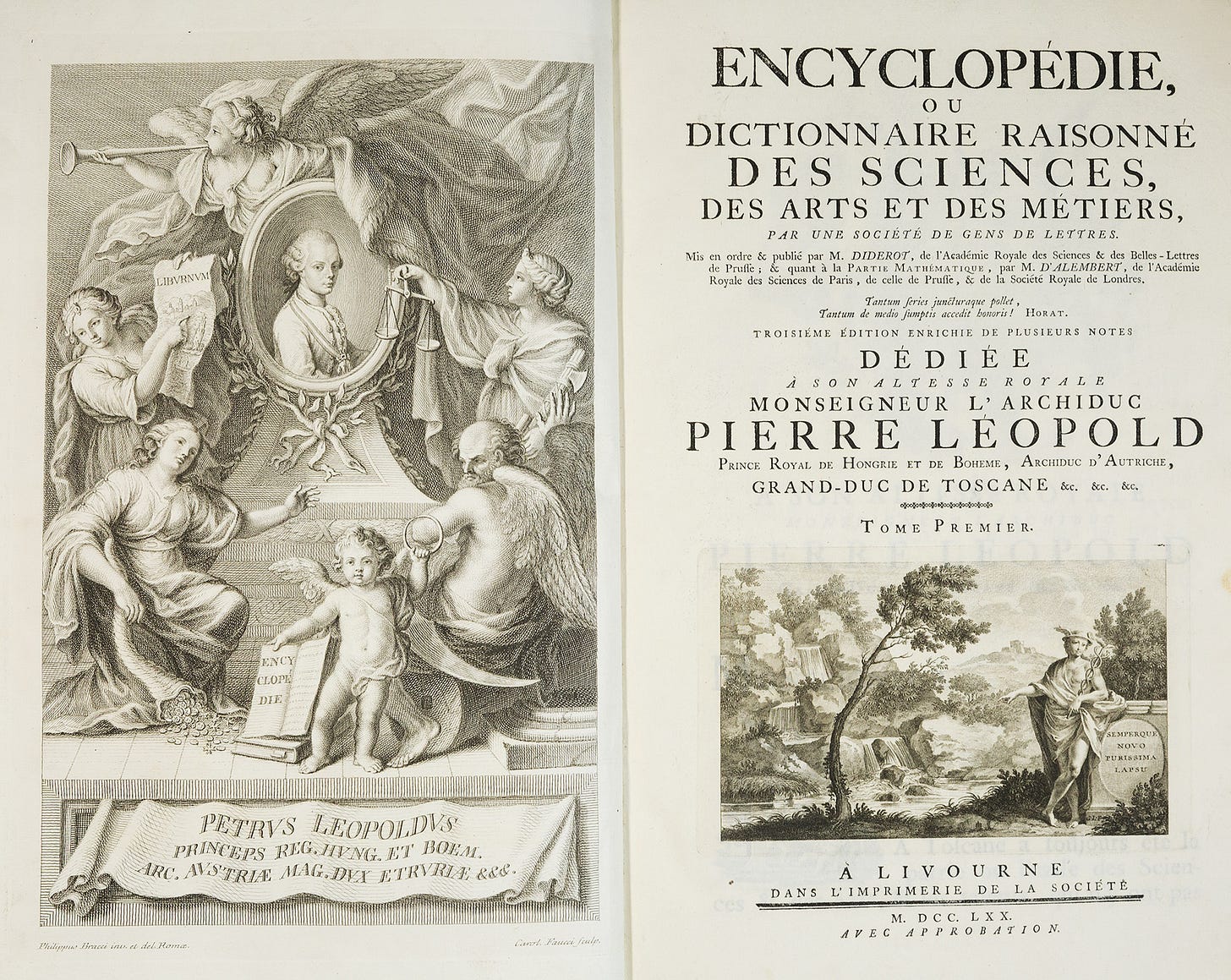

Today the encyclopedia as a concept is commonplace, even outmoded, yet by being so obvious its true meaning is also obscure to us; only an ontogenetic account can shed light upon such a phenomenon. Perhaps the first such form was Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia, published in 1728. More famous, however, was that first intended as a French translation of this: Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Enyclopedia, or ~a Reasoned Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts). This is the plain source of our word, of which the root refers back to an ‘all-round education.’ But more, we might note that this is a dictionnaire raisonné; here is our first clue to its particular distinction:

It did not merely provide information about everything from A to Z; it recorded knowledge according to philosophical principles expounded by d’Alembert in the Preliminary Discourse. Although he formally acknowledged the authority of the church, d’Alembert made it clear that knowledge came from the senses and not from Rome or Revelation. The great ordering agent was reason, which combined sense data, working with the sister faculties of memory and imagination. Thus everything man knew derived from the world around him and the operations of his own mind. The Encyclopédie made the point graphically, with an engraving of a tree of knowledge showing how all the arts and sciences grew out of the three mental faculties. Philosophy formed the trunk of the tree, while theology occupied a remote branch, next to black magic. Diderot and d’Alembert had dethroned the ancient queen of the sciences. They had rearranged the cognitive universe and reoriented man within it, while elbowing God outside.1

Yet the underlying epistemology here is somewhat more complex than the simple empiricist formulation; the abstract philosophy differs from the actuality as social enterprise. Empiricism was what underpinned faith in knowledge, as crystallised in the doctrine of scientific method; yet this was not so much individual knowledge as that of the human collective—as represented by the Encyclopédie, compiled of the work of countless contributors. This locus of development was conceived by Hegel as his Spirit, and in this we find precisely the outcome of Diderot and d’Alembert’s manoeuvre: the self-deification of science—that is, of the human eye. But more than this, it is technical knowledge which emerges from this process. The eye provides the actual justification, but in reality it is socially-determined based on rationality and authority. This results not from any malevolence but by virtue of the division of labour which enables technical progress in the first place. The Encyclopédie as a physical object, a book or set of volumes, represents a form in which man’s knowledge (fragmented by time and the division of labour) can finally be seen to coalesce. This is, moreover, referred to as an ‘all-round education’—in which sense the object can be seen as something worn or even inhabited; it has the characteristic of being somehow encompassing. We can thus see the Encyclopédie from two perspectives: internally, it stands as an image of the whole; externally, this entering-into can be seen to contain the individual.

How can we attribute such power to a mere book? Somehow this all sounds too much like magic, perhaps madness; yet the world has known of such a book before, and in this can be seen a prototype for such a relation. This is seen in the model of Revelatory scriptures; as the Bible, Quran, etc. Here the Word is invested with something above mere human language; it is taken as Revelation, at which we encounter the truth of an architect in relation to his own creation. The Bible is not true in a merely accidental sense, does not speak as mere spectator or inhabitant; rather it is taken as entailing the essence of Truth. This comparison was not lost on contemporaries to the Encyclopédie’s publication; indeed, it was taken by many as a direct challenge to religious authority. Yet this is not a simple challenge as criticism or mockery, such entails heresy in the highest order. We might question that it was ever allowed, that perhaps the risk was not properly understood; or more likely, as evidence of sales suggests, that such a book merely reflected trends which were already well underway in French culture.

While initial printings of the Encyclopédie were prohibitively expensive, during which period it spread only among the elite, later editions brought the price within reach of most. This was not merely a case of increasing supply, as this narrative might suggest; rather its dissemination was driven by steady demand. The market was such that those involved in its publishing were at each others' throats to maximise their profits. If Diderot and d’Alembert were driven by a moral imperative, such cannot be said for the publishers; their imperatives were purely economic and greed drove them to all manner of immoralities. The Encyclopédie was a profitable endeavour. This suggests that the culture was already primed for such a text, that it served some symbolic purpose; it can thus be seen as a totemic form of the cultural shift. Nowhere need it be said that this caused anything, only that it reflected currents which can be seen to protrude also throughout the surrounding history. We might well see in the Encyclopédie a perfect symbol of this, one which reflects the fundamental inversion which was taking place: a tree is pulped, turned to paper—and on it is printed the tree of human knowledge.

We see in the Encyclopédie, therefore, a new imago mundi; at the centre of the universe we find a book—moreover, one produced and read by man. We see further within a particular worldview, though also variations by virtue of its many contributors. There are those that share the philosophy of Diderot, such who believe the world may take the form of technical knowledge; then there are those that express doubts and emphasise the importance of practical knowledge. This can be seen as a divide between symbols of knowledge: man and book. Practical knowledge resides in man, expresses itself in activity; may well be convertible into reflective discourse, but this is by no means necessary. Technical knowledge, in contrast, is that of the book; that which can be formulated into precise propositions, rules, formulae, diagrams, etc. Technical knowledge is that which can be seen; that which is derived from science, though we may take this on authority. Yet of technical knowledge, here we may point precisely to the certain form of understanding as crystallised in words; what has the bearer of practical knowledge? Perhaps they may demonstrate it by the exercise of some skill; still taste is hardly deemed knowledge anymore, instead is identified with subjectivity and nescience. This is a crude materialism, a world-image in which faith requires some sensible object.

There is much to be said on the topic of literacy, of the relation between world and word, on the currents of the Enlightenment and the Encyclopédie in relation to all these; that must wait. For now we might finish by anecdote of another book: Etat et description de la ville de Montpellier fait en 1768. Here we find a man attempting something quite unusual, for in this text it was his desire to render as text the “true idea of a city”—namely, that of Montpellier in 1768. In this effort we see a man concerned to note every detail of his city, filling over four hundred pages of writing to this end. Of this we may note that the city is reduced to images: first as a procession of the populace ordered by their respective positions; then by reference to architecture metaphor, in terms of estates within the city; and finally, in terms of the various styles of life therein. The world is reduced to printed text; yet in it we find only ourselve—that words are but a skeleton which our soul always must animate, to which we contribute our own flesh. What is the point of all this?

It stretches, this little trick of mine, from book to book, and everything else, comparatively, plays over the surface of it. The order, the form, the texture of my books will perhaps some day constitute for the initiated a complete representation of it.

Darnton, The Business of Enlightenment, p. 7.