We weave a world inward mirrored

> … the order in creation which you see is that which you have put there, like a string in a maze, so that you shall not lose your way.

There is a higher and lower realm, sensible and imaginal—but which way does the mirror run? We see a symmetry between worlds. The skeptic cannot take the day when people still stand and speak. Somehow there is a similitude between these two, a correspondence or coherence that allows their meeting. They are as emanations of the isthmus between, constituted as against the sea on either side; an instant of solidity that, for our purposes, conditions the whole.

These two, higher and lower, however, are no mere categories; or not of any ordinary sort. They reflect the ground of existence itself, the very possibility of anything prior to either is situated here as a blunt imposition. This is the ‘is-ness’ of which people so often speak madly. We speak of the being of things mental, say, which seems sound evidence for their actuality. Yet these are actual only through their being enacted; indeed, they are realised before and after.

We began: Which way does the mirror run? Here we may roughly contrast two crude classes, materialists and idealists. The idealist says that the world is an emanation of ideas; the materialist that ideas are ‘emanations’ of the material world. There are further those that assert a simple unity of the two, that ideas are the world. These are all each inadequate solutions; all are somehow true.

We must see that, certainly, ideas are emanations of the sensible world. This provides the clay from which imaginal forms are made. Here we may see that the ideal is formed by the material, at least in providing the form of thought. There is a limit: the unimaginable. We must not presuppose that all that is thinkable is all there is. This is the insight of the materialist, that the ideal is limited and ultimately dependent.

This emerges plainly in its philosophical aspect, that there need thus to be a variation of fundamental method according to this perspective on the imaginal. Reason is limited in its play to the possibilities provided by the sensible realm. There are things we cannot think, for there is nothing like them; nothing to which they can be compared. This is the hard limit, though there are also lesser forms. Our finitude, however, is everywhere evident.

Take the mobility of existence, say, of the sensible contents of experience: of this, if you know what I mean. The page is frozen, yes—and here so am I—but everywhere around you there is a mobility and impermanence. We freeze this world, vivisect and represent as taxidermy. The lion roars no longer in our thought, though perhaps we may try imagine this. Bohm wanted to verbify language, to move away from the partiality and false solidity of nouns. This was an effort to overcome the fragmentation and immobility within the bounds of language. I am not sure what to think of this.

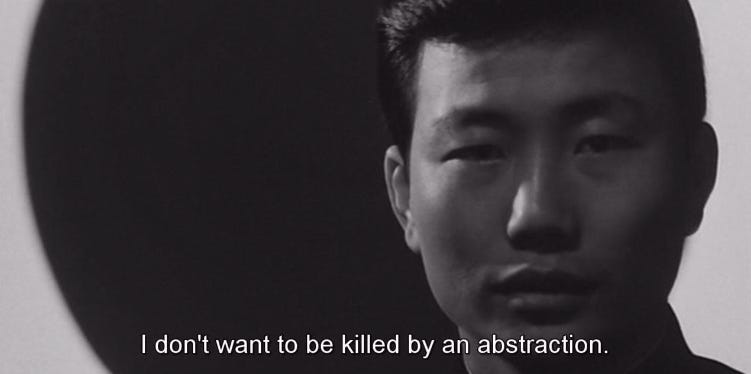

This line just followed is true, of course, that the ideal is ‘emanation’ of the material; that it, moreover, is limited by the forms which the sensible presents itself. Yet we must admit also that there is a return journey, for thought does not float away; it tends often impress itself once more upon the world. The forms of sensibility give rise, for instance, to the narratives we tell in order to put forward a possibility. We tell a story so as to convince another, or ourselves, and then in the corresponding enactment the ideal is actualised. This is the way that, say, a nation may kill a man; despite it existing foremost as an idea rather than actuality. John Bull may not step out of the page and execute us but his servants can accomplish much the same. Ideas are most important in assemblages of human servitude; as best reflected in the enterprise of the modern state. There they serve as the nervous signals which structure, whether more or less effectively synchronised, the movements of this vast leviathan.

The ideal exists, moreover, in the various plans and written inscriptions which circulate throughout the modern bureaucratic war machine. All statehood, of course, is akin to war in its seeking to impose itself upon the world. This entails a violence irrespective of the presence or absence of blood. Here the design for a new highway, for instance, entails a violent imposition upon the landscape as much as the people that currently inhabit the desired area. The plan will echo through the organisation, down and out through hands that drag the homeowner from his property or cut the ribbon at an opening. All of these are instantations of an idea, of that there can be no doubt, and the effects thus realised are of a marked magnitude. The world today is constituted more and more by ideas, or at least purports to be thus. We have come even to think the world in terms of ideas realised as objects and entities; a phone, computer, airport, taxi, whatever.

Yet we forget that our activity co-constitutes this existence, that the meaning of a thing is determined less by its design than the possibility this form presents to us. The world pretends to solidity, whereas everywhere the actuality of these ideas is composed of a sea which never truly repeats itself. We must remember that it is not objects that are standardised, rather that we standardise ourselves by the possibility we take as embodied in the object. The imposition occurs only to the extent that we allow ourselves to be funneled into an intent thus embodied as activity or otherwise physically—or rather, to the extent that we ourselves realise this.