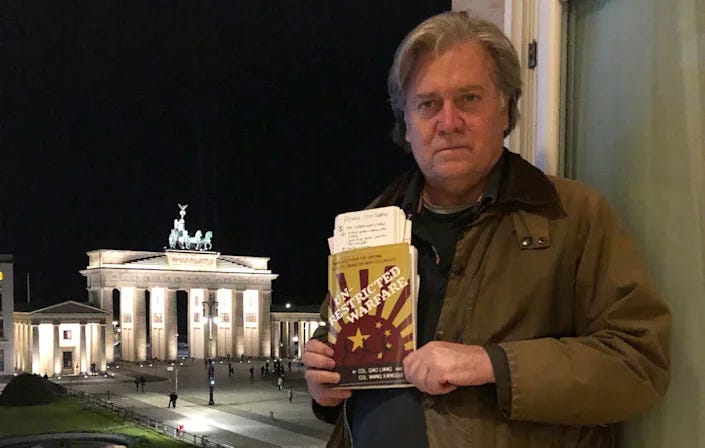

Unrestricted warfare

Breaking from my usual bullshit, some commentary on current events.

The war in Ukraine is particularly interesting not because it is somehow more abhorrent than, say, the United States’ involvement in Iraq or Syria; it is interesting because the major parties are somehow playing two very different games.

The Russians are either totally insane or operating rationally according to their geopolitical interests. Whether this is in their long-term interests is a matter of perspective, but we can see how they might have a fair desire to keep a hostile alliance from acquiring a partner right on their border.

The Ukraine is, for our purposes, not so much a real nation; it is a puppet in the play of incentive structures. There is somebody else playing a game here, and for simplicity we can call them the United States. A play is being put on, then what is the script and who are the audience?

We might as much call this play an act of war by other means; it is informational warfare which seeks not geographic but narrative control. The ‘audience’ are its intended targets—who are they?

Here we must remember, first of all, that media is a more or less indiscriminate weapon; a story can be picked up and bounced anywhere in the world. Whether it does so will depend on the coherence between this and the worldview of the operating agency. This could be as small as a single person posting a tweet or as much as a story picked up by a news agency. The editorial team will run stories which are coherent with their audience's narrative; hence the medium determines the targets.

There is a second sense, however, whereby the intended targets may be defined more specifically. Perhaps there are those in Europe who have come to distrust the United States, they may see a coming age of multipolarity and be considering a more flexible foreign policy. Smaller nations have always benefited from the capacity to play great powers off one another. This allows them a measure of independence with careful diplomacy, an equaliser of sorts for those that may be lacking in material strength.

The intended targets, therefore, can be seen here as any that might seek play against the United States. Hence the point is to demonise Russia and render friendly relations with them a politically unpalatable option. This must be kept in mind when assessing the behaviour of Ukraine—not only now but in the events leading up to the current crisis—in particular some apparently reckless choices.

We can note, for instance, that the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence is openly calling for citizens to create and use molotov cocktails against the invading forces. This is an easily produced weapon and yet one with certain limitations. For one, it can only be used quite close to the opponent; certainly close enough to be within rifle range. While the Ukrainian citizens may inflict a fair few casualties with the early surprise, the Russians will quickly adapt; it will require that they either accept a higher casualty rate or be much more aggressive out of precaution. They may even seek to deter further attacks by violence. All of this is entirely sound from a technical perspective—to say nothing of the moral. Any ethical limits placed here will negatively impact operational efficiency.

Taken amorally, we can see still that some ethical limit may be desirable from the perspective of optics. This will require a balancing act between casualties and the more difficult to assess harm, already considerable, on the international stage. More difficult will be whether the Russian soldiers begin to grow twitchy and fire first, something which even orders may struggle to contain.

A second tweet from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence, moreover, runs as follows:

There, the second to last line: “no age restrictions.” Last time I checked, child soldiers were reprehensible. Apparently this is not the case, yet here again narrative control is relevant. Here also the Russians will be forced to weigh optics against operational efficiency. Are they willing to kill adolescents and perhaps even children? I expect that at the very least some will be killed mistakenly, likely many more so than that. A child with a rifle is not a child, they are a rifle. The difficulty of isolating and subduing such an individual non-violently would be difficult, if not impossible, and come at a great risk.

Neither of these options are likely to be adequate to repelling the Russian forces. What is more likely is that both of these moves will, at most, delay the Russians and result in disastrous optics which can be leveraged two ways.

Earlier I said that the Ukrainians were effectively puppets here, and while I hold to that we must see why they play along. The advantage here is that optics can be leveraged to purchase support from the international community. Attention is a currency insofar as it places pressure on, and creates an incentive for, foreign governments to talk shit, provide aid, or even pursue an intervention.

The second way in which these optical factors are relevant is insofar as they contribute to the earlier strategic considerations outlined regarding the United States' strategy of divide and conquer in Europe. Germany, for instance, are uncomfortably close to Russia; it may be possible to have them act against their own national interests (e.g., Nord Stream 2) by creating political pressure through media influence.

Of course, I don't mean to be flippant here. This conflict is a tragedy for everyone involved, as is all such violence; yet this is also an important case study for the nature of modern warfare. The United States can be seen in this sense as using a proxy to wage an information war against the people of Europe, and even globally, even those within the United States. From this perspective, the game is something else entirely:

In the Gulf, in the same manner that the U.S.-led allied forces deprived Iraq of its right to speak militarily, the powerful Western media deprived it politically of its right to speak, to defend itself, and even of its right to sympathy and support, and compared to the weak voice of Iraqi propaganda, which portrayed Bush as the “great Satan” who was wicked beyond redemption, the image of Saddam as a war-crazed aggressor was played up in a much more convincing fashion. It was precisely the lopsided media force together with the lopsided military force that dealt a vicious one-two blow to Iraq on the battlefield and morally, and this sealed Saddam's defeat.