Time as rhythm and structure

An article from elsewhere.

First there is the breath, as steady unto death as its cousin, sleep. And wake again, as with day and night, as with tomorrow: the cycle of the sun, the first clock.

c. 1350–1400, Middle English clokke, clok, cloke, from Middle Dutch clocke (“bell, clock”), from Old Northern French cloque (“bell”), from Medieval Latin clocca, probably of Celtic origin, from Proto-Celtic *klokkos (“bell”) (compare Welsh cloch, Old Irish cloc), either onomatopoeic or from Proto-Indo-European *klek- (“to laugh, cackle”) (compare Proto-Germanic *hlahjaną (“to laugh”)).*

And far below: us. Long we lived only in the sun’s light, then came fire — Prometheus deserved his fate. We thought ourselves its master, really we worshipped fire where once we had the sun. Eventually it came to reshape us in its image. It taught us things, even made us smarter. We lost what we forgot, became reliant on this new power. All the while we thought fire under our control — no, the house always wins. And fire brought with it friends, all served the same lord. Energy now rules the world far more than intelligence. It has made us far more efficient, our technical progress also serves this end. Fire let us make more efficient use of the day, also of food. We used it to cook and this changed our bodies, made us dependent. And fire gave a gathering point, a first sense of self and other amidst darkness. Perhaps these early experiences explain the enduring notion of us and them — of light and darkness, known and unknown, order and chaos. Here we referred to things unseen, made known the unknown in our minds. We referred to the invisible by pantomime, as in the early iconism of sign languages. Thereafter by elaboration and creative combination we come to express more abstract objects, eventually even mere entities.

When we abstract we draw the flowing movement of actuality into a stable fragment. This we can then communicate somehow to others. But more importantly, we can reason with and act upon it in the world. There are also even more abstract entities on which we are unable to act, at least not immediately. These exist mainly as speech acts, only of utility in purely verbal activities — although perhaps with some possibility of complex output. We may never act upon freedom, for instance, though we may use it to get from one place to another, and there we may well act. But below this there is another layer, that realised in immediate experience as objects of perception. These are not simple objects, more than mere items or tools this entails also others — whether as individuals or tokens of a type. And below this, there is one final aspect: actuality itself. This is the undivided wholeness in flowing movement which grounds our experience of reality as understood. It is the seafloor of thought, where even the radical sceptic stops short. Though Descartes doubted even this, Moore still pointed to his hands. Or as my friend Darryl says, even a radical sceptic gets out of bed in the morning. For here Descartes’ answer, cogito ergo sum, is now impossible — God can no longer guarantee the actuality of thought. Rather we find, as Moore, that it is our embodiment of which we are most certain.

And here, too, we find a clock. For we are children of the sun, it made us long before fire intervened. Our bodies, made in its image, seek harmony with the solar cycle. But we have tricked them by fire and artificial light, falsified the sun for our own ends; or perhaps, the ends of some other entity. We may think of tools as enabling our activity or equally as determining our possibility. They give the shape to which we conform in our choices, at least where our interests align. And this fire has certainly done, as does anything sufficiently embedded in human culture. (See the variation in lactose tolerance among peoples with historical access to dairy.) But here we will focus on light and time, two interwoven instruments that define the structure of human activity. It is perhaps the solar day that first gave us an understanding of bounded times. And beyond this, albeit a little more abstract, there are also the seasons. It is the daily cycle that first defines our experience. Inuit timed their journeys not by distance but sleeps. We too define our journey through life by sleeps, as days or some larger unit thereby comprised as months, years, etc. But where once the day was set by actuality we have imposed artifice and abstraction. Seconds, minutes, hours, even days — all this has become quantitative, time rather than timing. Where Kairos reigned for the Inuit, we elevated instead the ever more rigid face of Chronos, of time as quantity.

We have taken away much of the meaning of day, constantly push ourselves to the limits of embodiment. Artificial light extends the useful hours and allows activity to continue where night once put an end to most. And hence we have deformed also our biological clock, with our circadian rhythm now entrained by this false light. It is as if we have short-circuited our standard system. Instead of darkness signalling our biological clock to sleep, now we hold the night at bay until we decide to sleep. This we do by reference instead to abstract time, that of clocks by which we coordinate social activity. We may listen to our embodied experience, as when we are tired, or we may suppress this too with caffeine and other substances. Ultimately sleep will always win, however hard we may fight it. Throughout we have aimed to seize from actuality control over the rhythms of existence. But alongside this we have also sought another aim, one which has not meant individual freedom. Rather social time reflects the imperatives of technical progress, ever reaching for greater efficiency. This has meant a standardisation of social time, one which overrides all particularities and forces them to conform. Most thus work from nine-to-five, five days a week. This is the central structure of daily existence in modernity.

But this structures gives only what it must, only what efficiency demands. As yet it rarely reflect variations in individual chronotypes, instead favouring larks over owls. An argument can be made that accounting for this would increase efficiency, already has been in places. The logical system may find good reason to slacken some in the face of this. And yet it will never do so simply for the benefit of its inhabitants, only ever for its own efficiency. At best one can make an argument what would be good aligns with what would be efficient. This is surest line of success for any that would oppose the strictures which modernity imposes by way of technique. For man, though born free, is now found everywhere chained by reason. And for good reason, it is said; for the economy, prosperity, progress. All this has freed us from the irrational forms of actuality and tradition. Man has come to claim mastery over all nature, even over himself and others like him. This rational ordering of existence has wrought truth from artifice, has shaped the world in its own image. But this image is never more than idea imposed upon actuality by technical means. It is as a simulacrum: a copy without an original. And this rational order, no less than had tradition or nature, still more or less rigidly structures our existence.

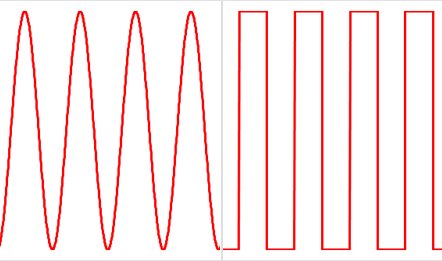

Today, however, the new world order cares little for the rhythms that once animated traditional forms. What rituals remain are almost entirely economic, all values are now expressed as a quantity of money. And beyond this, still there are cultural rites — as the popular superstition wherein people vote as a mass charm against bad luck. There are others, also, but these barely bind with any moral force and are themselves largely reduced under the umbrella of economic exchange. Everywhere today man serves Mammon. This new god is not of our image, instead remakes us in its own as mere quantity; what cannot be counted does not count, what cannot be bought has no value. For this is the time of no room: neither for Christ nor wholeness, let alone the rhythms of which life is truly composed — the Song of Songs now a digital signal.