The many faces of time

An example of metaphors and many-sidedness.

Here we have seen metaphors as figures of thought, ways of apprehending the world—otherwise indeterminate, an undivided wholeness in flowing movement. Metaphors ‘carry across’ our understanding from a relatively concrete base domain (e.g., a river) to a more abstract domain (e.g., time)—thus we can understand time, for instance, as a river. Of course, this will highlight aspects coherent with this understanding and hide those that are not.

Take, for instance, two Greek gods of time: Kairos and Chronos. These are strictly speaking personifications of time, yet we find everywhere that such ideas often begin as deities and are then further abstracted. For our purpose, these are the same as that with which we have been thus far concerned.

Kairos is depicted as having a single forelock, that by which one had to seize him as he moved quickly by; in this represents time as in timing—the time of opportunity. Chronos, in contrast, is a more complex character; particularly in his relations with Kronos. Taken simply, we can think of Chronos as quantity and duration; whereas Kairos emphasises the quality of a period or point.

Hence when inquiring as to the nature of time, we must keep in mind the Jain principle of anekāntavāda: time is many-sided. Thus far we have covered just two, though there are many further; even within the Greek pantheon there is also Aion, Janus, etc. For the remainder of this piece, we will consider time not from the perspective of personalised aspects but instead in its basic metaphoric structures.

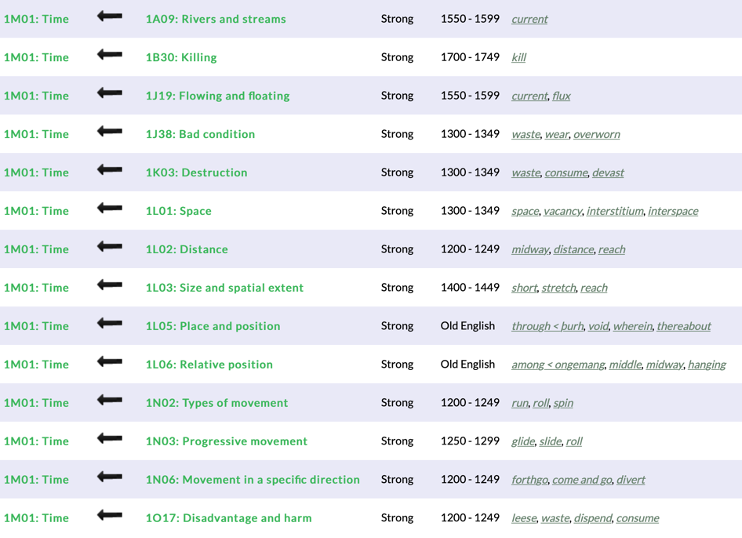

The above image, from Glasgow University’s metaphor map, shows the direction of movement in metaphors for time. Time does not structure any other concepts, instead it is consistently the target domain of a variety of material metaphors—distance, flowing, position, etc. We will here run through the basic structural metaphors for time as outlined by Lakoff and Johnson.

Spatial orientation

That’s all behind us now. Let’s put that in back of us. We’re looking ahead to the future. He has a great future in front of him.

This metaphor likely seems intuitive, almost obvious or even necessary, to us. And yet there are several variations of this, wherein the basic spatial mapping is retained while the specific orientation differs. In Aymara, for instance—a Chilean language spoken in the Andes—the reverse is true. There “past time” is mayra pacha—mayra meaning “eye,” “sight,” “front” and pacha, “time.” And future time is q’ipa pacha, where q’ipa means “back” or “behind.” The experiential basis of this is akin to Kierkegaard’s comment: “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.” When we have done something, the results are visible before us where they can be perceived; whereas the future is unknown, cannot be seen as with the world behind us. While this formulation may seem counterintuitive to us, there is no way to say that one is more correct than the other—again, anekāntavāda applies here.

As a further variation on the above examples, most English-language speakers will lay out time according the structure of written English: from left to right. “Kuuk Thaayorre/English bilinguals,” in contrast, “represent time along an absolute east-to-west axis, in alignment with the high frequency of absolute frame of reference terms in Kuuk Thaayorre spatial description.” This suggests that while metaphoric understandings are important, they do not exhaust the structured relationship between time and space. There are no specific metaphors in English, for instance, that refer to time as moving from left to right. This is simply a part of the wider experiential landscape, as in our writing and reading from left to right, and reflects a combined spatial and cultural influence on our conception of time.

This time orientation metaphor—for English, with the future in front of us and the past behind—is further elaborated on in two primary metaphors for time. These fill out the picture by drawing on our experience of motion in different ways:

In the Moving Time metaphor, the observer is the ground and the times are figures that move relative to it. In the Moving Observer metaphor, the observer is the figure and time is the ground—the times are locations that are fixed and the observer moves with respect to them.

Time and motion

The time will come when there are no more typewriters. The time has long since gone when you could mail a letter for three cents. The time for action has arrived. The deadline is approaching. The time to start thinking about irreversible environmental decay is here. Thanksgiving is coming up on us. The summer just zoomed by. Time is flying by. The time for end-of-summer sales has passed.

We can understand time as coming towards us from the front, passing by us—here and now, in the present—and moving into the past. We stand in a fixed position, facing the future, and time moves towards us; come, gone, arrived, approaching, coming up, flew by, passed. All these entail a metaphorical structure in which time is understood as motion towards, and past, the face of a fixed observer.

That we combine this understanding with that of time orientation further allows us to consider times or events as having metaphorical orientations, fronts and backs; and thus as preceding or following each other. These are here defined in relation to the fixed observer, as preceding or following this reference point: “On the preceding day, I took a long walk. In the following weeks, there will be no vacation.”

This basic model, that of moving time, can entail either a multiplicity of objects moving towards the observer or the flowing movement of a substance. The latter is exemplified in a common metaphor: the river of time. Here we can understand, for instance, duration as the extension of this substance; a lot of time has passed, or only a little.

There’s going to be trouble down the road. Will you be staying a long time or a short time? What will be the length of his visit? His visit to Russia extended over many years. Let’s spread the conference over two weeks. The conference runs from the first to the tenth of the month. She arrived on time. We’re coming up on Christmas. We’re getting close to Christmas. He’ll have his degree within two years. I’ll be there in a minute. He left at 10 o’clock. We passed the deadline. We’re halfway through September. We’ve reached June already.

Alternatively, we can understand ourselves as moving through time—with the future ahead of us, the past behind. Here the metaphorical mapping of motion is inverted: now it is the observer that moves, time remains fixed. Each location on the path ahead, again following the orientational structure already outlined, indicates a relative time. We thus see the passage of time in our movement, the time elapsed as distance travelled. Depending on how far we move, then, time can be measured; something may take more or less time. There may also be bounded containers on our trail, as when we arrive at Christmas or miss a deadline.

Time is money

While the metaphors discussed thus far have been concretely spatial, we may also understand time more abstractly, for instance, as a resource:

You have some time left. You’ve used up all your time. I’ve got plenty of time to do that. I don’t have enough time to do that. That took three hours. He wasted an hour of my time. This shortcut will save you time. It isn’t worth two weeks of my time to do that job. Time ran out. He uses his time efficiently. I need more time. I can’t spare the time for that. You’ve given me a lot of your time. I hope I haven’t taken too muchof your time. Thank you for your time.

This schema draws on elements of our experience with resources: expenditure, scarcity, efficiency, and so on. These aspects are apparent in the examples presented above. Most notably, we find the metaphorical use of language evoking more concrete resources—waste, worth, etc. Of course, this understanding of time as a resource probably seems as natural and obvious as the others we have covered. And yet here, too, there are cases where this metaphor is not apparent.

The Pueblos, for instance, have no expression equivalent to “I didn’t have enough time for that.” Instead, they say, “My path didn’t take me there” or “I couldn’t find a path to that.” This understanding paints a very different picture of our relationship to time. Suppose that someone missed a meeting with us and, by way of explanation, simply told us: “My path didn’t take me there.” We might well think them mad, or at the very least rude. This suggests that the dominant metaphors of time in a given culture shape not only our understanding of time but also our expectations of others’ behaviour—perhaps their Pueblo friends might understand, most of my friends would not.

There is already here a hint of morality in the use of time, particularly insofar as it is seen as valuable. We might accuse someone that misses an appointment, for instance, of “wasting our time.” Alternatively, we may praise someone for using their time efficiently—or criticise someone that does not.

There is, of course, a more specific formulation that extends this basic ‘time is a resource’ metaphor which is prominent in Western modernity: time is money.

I have to budget my time. I spent too much time on that. I’ve invested a lot of time on this project. You don’t use your time profitably. That mistake resulted in a considerable loss of time.

To begin, we should note that this metaphor is certainly not universal—it wouldn’t make sense to the Pueblos, for instance, for whom time is not even a resource. This metaphorical understanding of time as money extends that of time as a resource, with money singled out as a specific resource. Much of this structure is shared with the basic resource schema as outlined above, but it goes further including also words mapped from our understanding of money: budget, spend, invest, profit, loss, etc.

As noted, this metaphor obviously isn’t found among the Pueblos, for whom even the idea of time as a resource is foreign; and nor will it be found among those with no concept of money. We might ask here who is right, is time really money? This obviously cannot be answered in any metaphysical sense. What we can do, however, is note that this understanding is often real at least in a pragmatic sense that it is often something which must be taken into account. We find Western society has many institutions which reify our understanding of time as a resource or as money.

An important part of ‘Westernisation’ is importing this metaphor and the social institutions which reify it. People invest their energy as labour (resource) in exchange for pay (money); and we use money as a resource which may be invested, used up, and so on. The same is true of time, we may use it well in lucrative employment or somehow squander it, as by in leisure.

These metaphors—time as a resource, time as money—in other words, entail particular expectations for how people ought to handle their time: “Western businessmen seeking to set up factories in Third World countries,” for instance, “often see indigenous peoples who do not conceptualise time as a resource as being lazy.” And for those that wish to be successful in Western societies, there is indeed great deal of utility in treating time as money; it is this utilitarian truth, rather than anything metaphysical, which Benjamin Franklin sought to communicate by his maxim.

A short series on fundamentals, metaphors and many-sidedness:

The many faces of time (you are here)