God is dead. And we have killed him.

"Those trees in whose dim shadow / The ghastly priest doth reign / The priest who slew the slayer, / And shall himself be slain."

Or so said Zarathustra some time ago, though some controversy remains. See, nobody seems able to prove with any certainty that God is actually dead; indeed, few seem to know exactly this would even mean. Being a man of science, I suggest we first poke Him with a stick—quite firmly, you know, just to be sure—and then, hence the importance of his being actually dead, we might perform an autopsy. If we can see some cause of death, as perhaps a large tumour behind his eye or a hole in the back of his head, then we might be reasonably certain of his demise.

Of course, what does anyone of this even mean? That’s always been the problem: nobody quite knows. I will start by moving backwards: God is not a thing that I can grasp, nor is the earth entire or even as small a country as mine. Our hands are simply far too small. We thus obviously cannot grasp him by mind, either, for here again our hands are too small. And we are certainly not omniscient, as just the other day I was surprised to find a muscle that these whole fourscore years been hiding from me—in all honesty, I can barely navigate the palm of my hand.

Jesus, on the other hand—now that’s a fellow you can grasp. That’s why we love him, you know, because he’s a lot like us. Sometimes I wonder whether he was tender with his washing the disciple’s feet, did he give their tired muscles a little rub while he was at it? Personally I like to think he was as affectionate as he was serene. Anyway, the problem, of course, is that we definitely did kill Jesus. I was struck during Eucharist once upon hearing something that it seems Zarathustra hadn’t: “We proclaim your Death, O Lord, and profess your Resurrection.” The old sage must have been in such a hurry on hearing the first half that he was gone to tell everybody else before they got to the second! We will, nevertheless, continue our inquiry in spite of this revelation.

Seeing, in that case, as we aren’t even sure where to prod for signs of life, we might as well start with the autopsy. Now, forgive me, but there’s the bait and here’s the switch: this isn’t a fun essay at all, now we’re going to talk about boring stuff—any that wish to exit, now’s your chance.

The Psalter map (c. 1265) shows the world as cosmographia. Here my use of this term comes from the various translations of Ptolemy’s cartographic work: cosmographia, geographia. My line is that these are not the same, or that we may treat them as such. We have begun with the cosmographia, which constitutes an image of the cosmos. This can be seen most clearly in earlier maps, which represent this world as a bounded entity within a clearly defined cosmological schema. There is a centre, Jerusalem, and a boundary; it is not a geography but a cosmography, as reflecting the order of creation according to scripture rather than science.

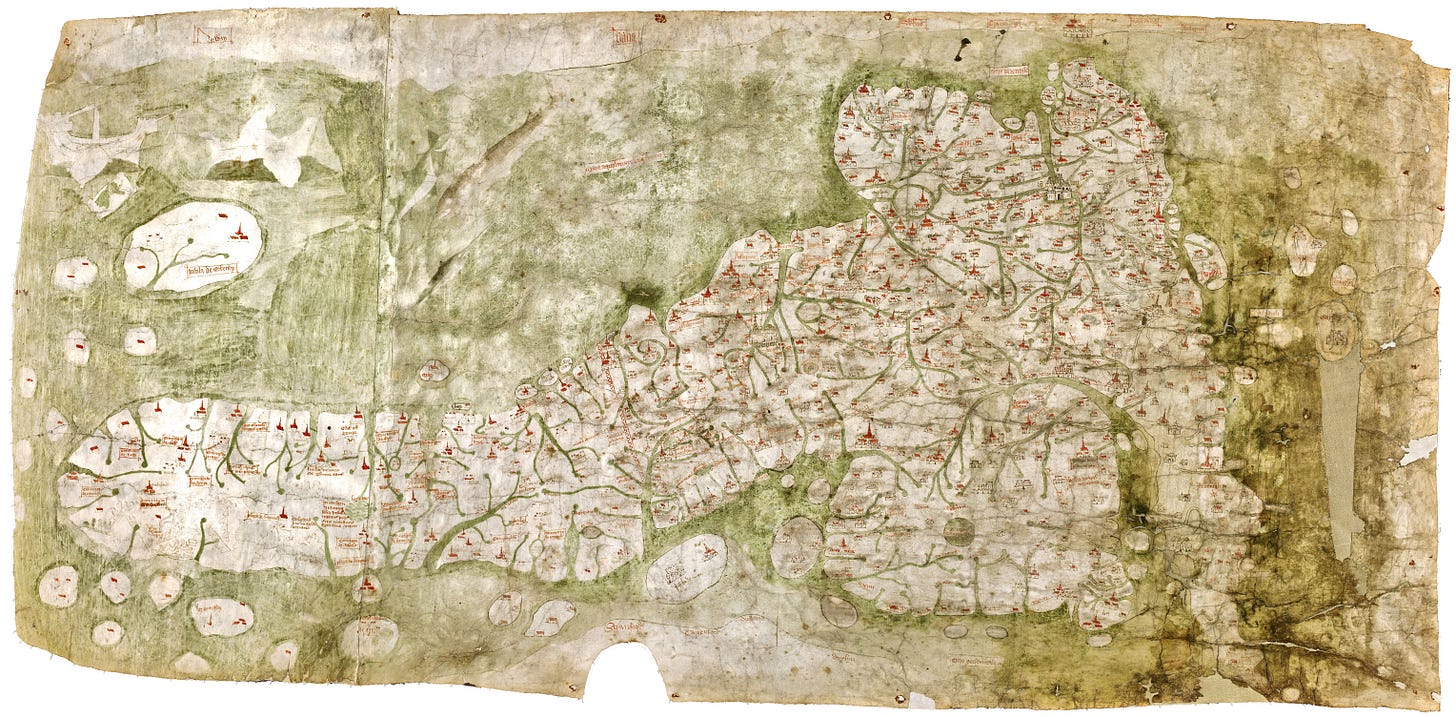

Subsequent to such cosmographic maps, we encounter a new form—as, for instance, with the Gough map (c. 1300). This we will characterise in terms of world as geographia; it represents a fragment of the whole, circumscribed according to power and ambition. The Gough map shows England as a political realm, thus showing an apparent displacement of the divine; it is an administrative world, in other words, a bureaucratic imaginary. This is an image, moreover, determined as by science, with the accuracy of scale corresponding to the presence of roads: better where there are more, otherwise far less so. The physical lines of political rule are thereby correlated with the cartographic.

These roads are particularly important, for it is they that carry political power from a centre; it is only thus that, for instance, a king might reliably put down insurrections in the provinces. These also allow the ready transmission of information and supplies, thereby serving to constitute the circulatory and nervous systems of the body politic. Prior to these forms, the ideal order which impinged upon ordinary life throughout most of the country was theological rather than political.

Here we find a key element in the mirror between politics and theology which Schmitt describes; it is not that politics is somehow separate, rather that the administrative came increasingly to displace the religious as a central ordering structure—and in doing so, the two were fused. The genesis of our that politics which Schmitt inspected, in other words, was as an exaptation of the theological function.

This can be seen clearly in maps, as the central perspective of cartography shifts from altar to throne; although there are cases between, as where the two are intertwined briefly before finally cartography takes leave to assume its now familiar utilitarian political form.

Noteworthy in this new form is the fact that the map exists as a fragment. Something similar is seen in the Portolan charts which also emerged around the thirteenth century. These charts apply to another form of sovereign: that of the ship’s captain. They again allow for the orientation of an individual within a technical regime, for as the captain rules his ship via intermediaries and instrument so also the king came to assume a like function with regards to the administration of his realm. The difference, of course, is that the realm remains in place while the ship is mobile; yet in either case, the centre is determined according to its sovereign.

The Portolan charts, as we have said, are as mere fragments reflecting the specific coastlines and harbours relevant to a captain’s intended course. They sometimes included gridlines, but these lines could not be readily coordinated between separate charts; each remained an image unto itself, as against the unified whole expressed by the cosmographic cartography.

This was to change, however, with the rediscovery of Ptolemy’s cartographic writings in Florence by a reading group comprising notables with an interest in learning Greek. When they ran out of texts, they sent two across to collect more from Constantinople. Though the two were almost shipwrecked—if only they had drowned!—during their return, they arrived back with a copy of the Cosmographia/Geographia. This provided an instruction in the projection of spherical coordinates. Indeed, more than this, it also provided to Alberti the key which enabled an explicit formulation of method for linear projection—a signal which arrived just in time to be amplified with the rise of the printing press.

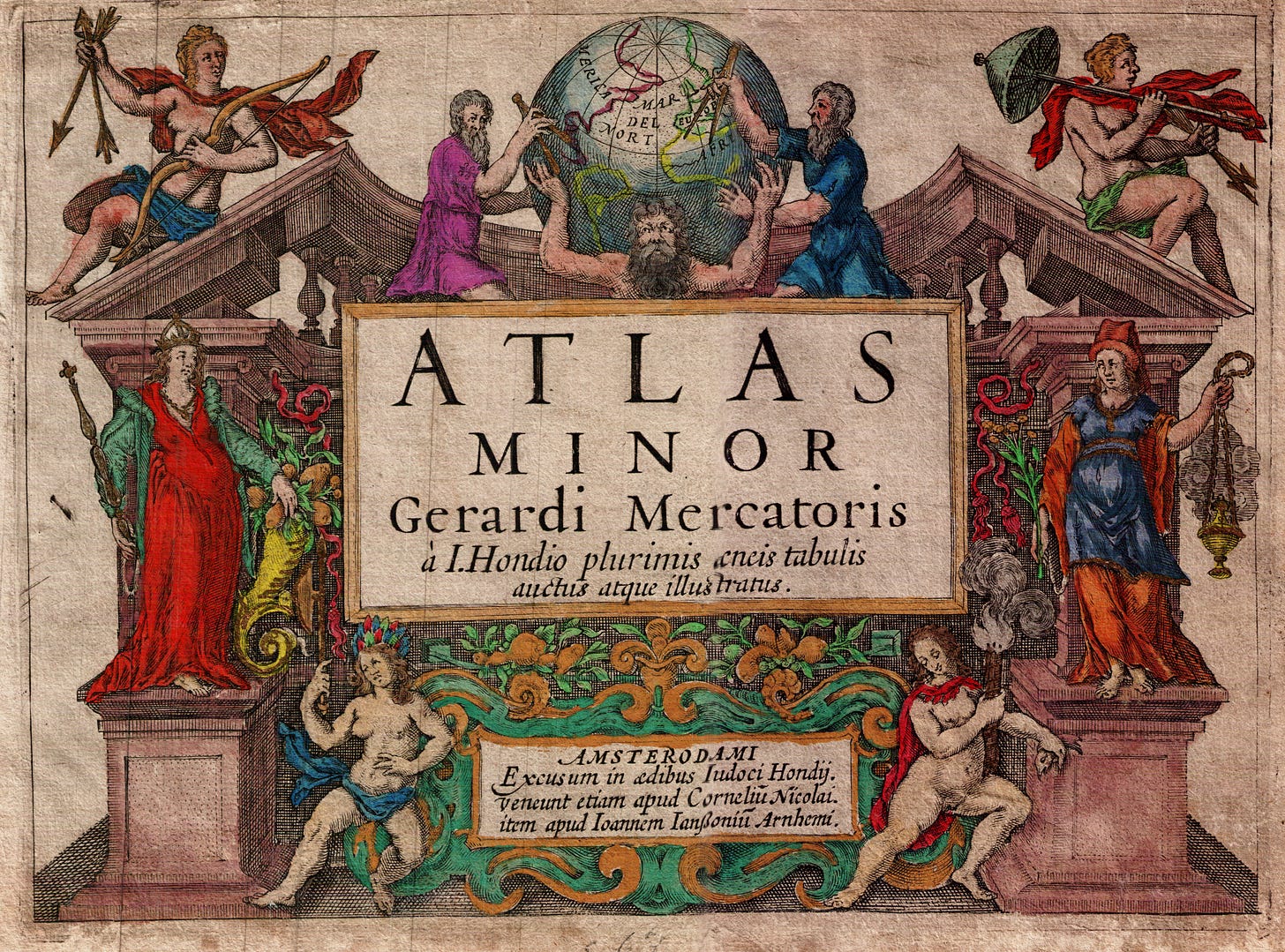

More importantly for our purposes, however, was that the fragmented geographic maps were now able to be united by way of a system of geodetic coordinates: that is, longitude and latitude. Here we see also a new symbolic form of cosmographia: the globe. The frontispiece to Mercator’s Atlas, for instance, has the Greek titan now holding not the earth but rather a globe.

Here we find man assuming a relation to the world akin to that which once God alone inhabited, as characterised by John Donne:

On a round ball

A workeman that has copies by, can lay

An Europe, Afrique, and an Asia,

And quickly make that, which was nothing, All.

Such positive notions of man’s station with regards to this advance ring clear in the somewhat bizarre theological writings of Nicholas de Cusa:

Thus man is God, but not absolutely, because he is man; humanly, therefore, he is God. Furthermore, man is a world, but not comprising All, because he is man.

At this, I might say, that had I been there I would have had Cusa tried for heresy—how such statements were at all acceptable is beyond me.

There is, moreover, a parallel aspect in this particular construction of space: that of the infinite universe. Here we find a second sense, though there are also those that marvel in the immensity of man’s conceptions. Giordano Bruno, for instance, saw the infinite universe as a mirror of God’s glory and positively revelled in the idea:

Thus is the excellence of God magnified and the greatness of his kingdom made manifest; he is glorified not in one, but in countless suns; not in a single earth, but in a thousand, I say, in an infinity of worlds.

The sense here, of course, is that which finds full form in the reduction of space to quantitative coordinates; it is that space, now geometricised, assumes the infinity common to its numerical bases. Yet the same basic image is latent in the Gough map, for instance, as well as Portolan charts: it is the absence in which these fragments float, and whereby they are invisibly united, which promises the infinity glimpsed by Bruno.

This explains, moreover, Kepler’s comments such advocates of infinity as Bruno, who “as if inspired (by some kind of enthusiasm) conceive and develop in their heads a certain opinion about the constitution of the world.” Yet we might ask whence this notion arises, for such a thing is odd indeed; is it not the same image which we have seen brewing in the maps of history?

There is further a reason that this is no mere novelty, as Kepler notes with concern:

This very cogitation [of an infinite universe] carries with I don’t know what secret, hidden horror; indeed one finds oneself wandering in this immensity, to which are denied limits and center and therefore also all determinate places.

The universe as quantitative infinity entails the dissolution of qualitative order; it is in this form that geographia is transmuted into an inverted counterfeit of cosmographia. The cosmos is reconstituted in the image of man; it is rendered as virtual reality for the purposes of political administration. This is the same mode of relation which Simondon posits at the birth of encyclopaedism, whereby the world is rendered—in a palpable symbolism, as ‘voult,’ referring to “a wax or clay image or doll of a person used in witchcraft or voodoo to affect him magically”—and thus represented by way of encylopaedias and atlases, maps and globes, paper and inscriptions:

Magically, everyone is master of everything, because he possesses the voult of the whole. The cosmos, once enveloping and superior to the individual, and the social circle constraining and always eccentric with respect to the power of the individual, are now in the hands of the individual, like the globe representing the world which the emperors carry as a sign of sovereignty.

Thereafter the only centre that remains is that from which worldly power flows, now an earthly empire rather than the kingdom of heaven; it is to this that we must attribute the notion of a ‘new world order,’ for here we find an image sure to fascinate such ambitions. These maps, after all, are made real only via the power realised through them; a man makes real his maps by way of the networks of actors that constitute his rule: tax collectors, policemen, soldiers, etc.

Here we find, therefore, not only a possible cause of God’s death—an apparent cancer of the administrative realm—but also a compelling motive, supporting Nietzsche’s allegation as to the culprit: it is we who have killed Him.