Fragments on language and architecture

Just as an architect, the writer must consider not only the external form of the structure they design but also the interiority of those that will inhabit; that is you, dear reader. There is in language the material symbol, as the words on this page; and the ideal form, as that which you enter into. Take the individual that knows no English, for them the material symbol remains, yet no ideality is possible outside of understanding. As with architecture, the experience of this ideal aspect will depend on one’s prior knowledge, experiences, mood, etc. One may associate high walls with the claustrophobia of a prison, for instance, or with the compound where one felt safe; so also with language. The world is tinged always, as in language and architecture alike, by the sediment of the past.

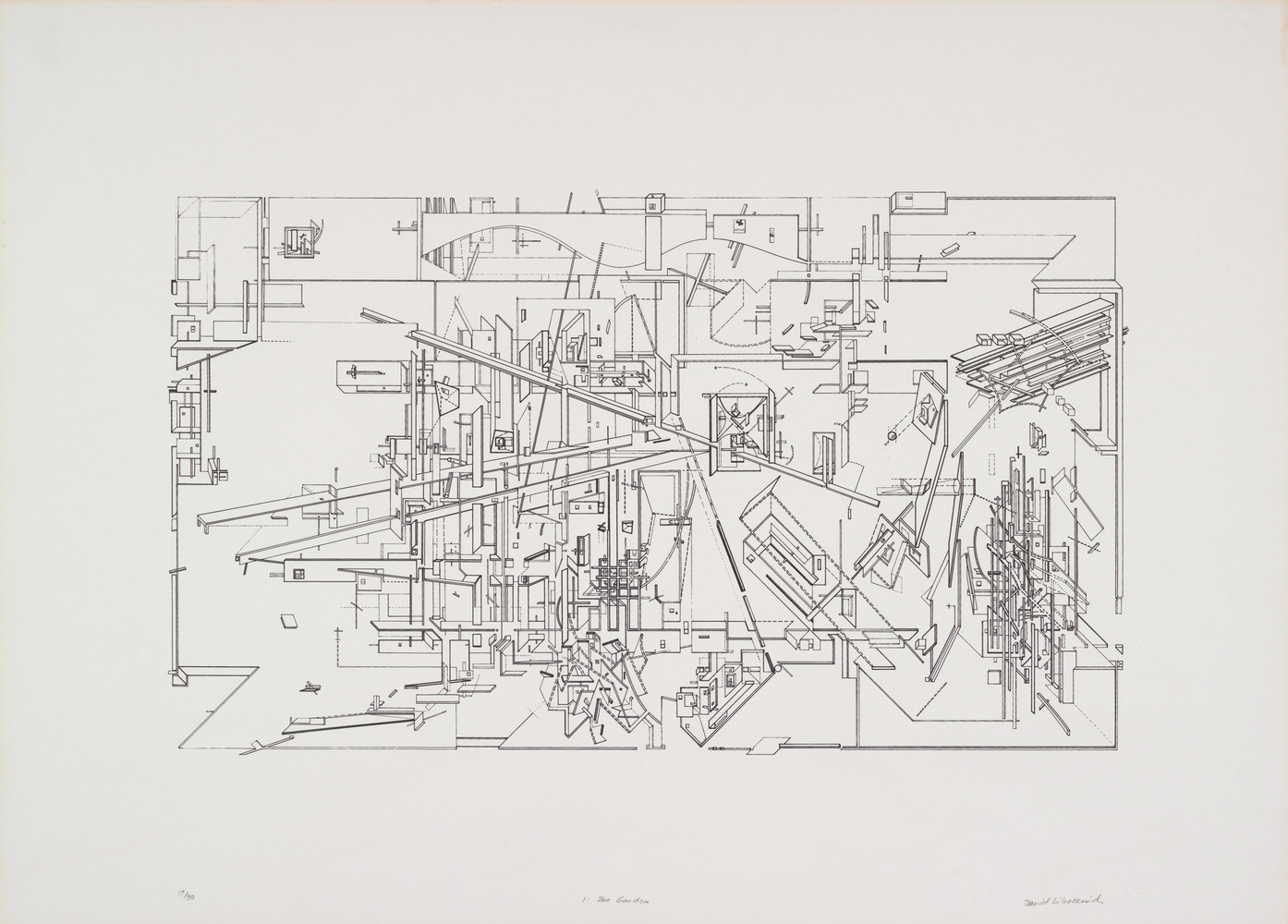

We might think that form and content are separable, yet consider the presentation of an artwork; can we ever separate entirely the item from its environs? So also in language, where we inhabit a place it ought align with the content presented; incongruence will only detract from the effect. One may write, for instance, of the most terrible atrocities, yet to do so an academic style is to risk killing even death, mere statistics and abstractions hold little sway over the heart. What is your intent? Yet also there are subtler effects, as when we convey ourselves unconsciously by the punctuation we use. See, for instance, the looseness of linkages conveyed by use of the em-dash. Throughout much truth of interiority can be found in the external form of punctuation. This is not so much to do with rules of use as it is feeling out the distances and angles, understanding their appropriateness to the line at hand, etc.

As one would not wish, or so I hope, to have their home designed as from a box set, so also style guides are mere training wheels. There is some value, to be sure, in learning the way in which tools work; yet this should not be considered an ultimate aim, rather that in gaining confidence one picks up speed and then—all of a sudden, finding oneself flying down the road on our own. Yet as with riding a bicycle: if you stop to consider yourself in the moment then you’ll likely stall, fall, etc. Creativity is the dialectic between an unknown surge from within, from whence ink first spills forth onto the page, and the careful application, and progressive refinement, of taste; only with time is the unconscious tongue sharpened to suit one’s taste, as it in turn is refined. Of course, if you are working somewhere that asks of you a specific style to which you must conform; then I am sorry, this is not so much for you.

My father, in thinking to design a house, spent much time travelling to visit such examples as he liked. Here he was refining his taste, yes, to determine what he did and did not like; but also he was letting all these things sink into him. So also for the writer, as one might try on the skin of a writer admired and seek to realise some aspect of their voice. While it will always be, at end, your own voice, still you might take on the tones of another. I speak with a strange accent, for instance, because so long I associated with a strange person. We become those we spend time with, and this is as much true of writers as houses or friends and family. For my part, I find Kazantzakis and Chesterton to be particularly inspiring; you will have your own, finding in those you admire a piece of yourself, then somehow seeking to realise this.