Child

> Night of your birth. Thirty-three. The Leonids they were called. God how the stars did fall. I looked for blackness, holes in the heavens. The Dipper stove.

The man was back again, drunk again. This heard from the cloud surrounding footsteps rolling down the stairwell. There the child sat in darkness, listened above. She had been here some several years now, knew enough of his rhythms to understand this shape. The day had been as follows.

He had woken early, immediately checked his phone, saw nothing, sought else and saw nothing there either, sat naked in bed and stared at nothing, an empty expression, scrolled through mindless without reacting, a snort at most here or the hint of a smile flitted across his lips. This was the way he woke each day, not from pleasure necessarily, even that a sadness, a hollowness, came of this, rather from falling simply through some rut, the same shape repeated throughout the day, again the same, a hollow thing yet repeated incessant. This the way he started his mornings until at last the hollowness had encompassed him, until at last he could taste it in the back of his mouth, the dry and stale breath of dead air, recycled breath, then he would throw down the phone and swear to forgo this rut, recall his former promises, swear again despite himself, despite his doubt.

This the shape of the morning, or most mornings, apart from those that came just enough to be a promise, just enough to seem something else, that those days he would leap from the bed, would throw himself into the day, would strike out sailed taut and dragged forward until at last some doldrums would return him to his listless point of departure. The doldrums then, what was his crime.

So the day began as always, that there he would see the shapes he would be, could be, or most that he would not, which he despised, but even this gave him little any longer, less by the day, that there was not enough energy in him anymore to even strike, only in abstract, that he retreated back into the realm of images and daydreams, that in this fantasy he struck the mass entire, all without ever lifting a hand, all without the energy necessary for a single act. This lifeless image, an empty ideal.

There was work to be done, always this work and that, never anything in particular, never an order to the process but for that impressed by panic, a set adequate to sustain him and then the dreams which he wove around this, all that he wove around this to paint himself, to colour himself some other way. These threads of gold he wore, which in the darker days seemed only gaudy, which in a softer light were all that got him by, and the pretensions that these were made of, all of this was the core of his being, so he felt, and to strip this away—well, what then would there be, what then would he be, not even naked, a skeleton, less than, a gust of air just passing by.

This ephemerality contradicted by the activity necessitated by sustenance, by the flesh which seemed yet false to him, by the activities required by existence. These the sole thing felt worthwhile and that alone for physiological cause, that curse the world as he may still hunger held his heart. These simply facts, that there was even some comfort in this, that he would hold himself from urinating for hours, however long, for time then seemed to stretch as well as his bladder, for then in this tautness, for the accumulation of energy in his groin, that here he felt some sense of fact remained. There was truth to this, direction, certainty. These the things he lacked were found sufficient at only the cost of his kidneys, some vague cost, a thing heard of but not understood. He thought that his addiction, for perhaps it was, that this was the coward’s equivalent of any other, that in their substance of choice, in the acquisition of this, in its effect, that here alone there was enough of a life for anyone, enough of meaning, that the addict was primarily addicted to this. They at least had a reason immediate upon waking, an orientation in life, tasks which pressed with the certain state of physiology, a material existence, that they were not alienated from themselves; though that perhaps this being some inverted counterfeit, that somehow the words were lost in this saying—and yet, no, that they were brought in line with themselves in this way, that they felt their labour immediate, a return to tradition, the addict a hunter-gatherer of old, cans upon the wayside, whatever it took, and then like those nomads also, days spend in quiet reverie. He had read once of the workload prior to agriculture, felt that the addict had returned to this Edenic state.

His was no such addiction, cowardice came first, but it was something, it held something of that fact, and so he held to this, warred with himself, held onto the single certainty of that fact: I need to piss. This at least I need, this I know. This the way he woke each day, and then the pleasure of everything else doubled, that in acting otherwise he found a way to avert himself, that this thing a magnet which pointed his attention inwards or pushed it away otherwise, the greater pleasure of a thing when others pressed. The play he held with necessity, until at last, at last it would be too much, and he would throw down whatever he had, whatever sleep he had woken with, would throw this down and stumble naked from his bed, eyes half-closed would clack the toilet seat against the wall, turn and lower himself into a fall, forearms rested upon his knees, release.

This was the way each day started, always the same, and always this excess of waiting, of out-waiting himself, for when night came he would need to urinate and then would not, would push himself to sleep despite this, would hold against that fact, would refuse existence, at once affirmed and rejected necessity, at once felt the assurance of its truth and enacted its denial. He had never once pissed himself in the night, though he felt that with age, were it given, which often seemed in doubt, yes, that with age surely he would piss himself eventually, oh to be young again, and yet this the other side of that curve, his parabola now descends as arrow sure to target.

Where would he go in the day? What did it matter, the child never knew. The child knew only that which was heard in the movements within the house, that rarely when he went beyond the door then it would be something else, and when he returned in whatever state, always alone. The child would wait for him below those stairs, there in the dark, the man who was her warden here.

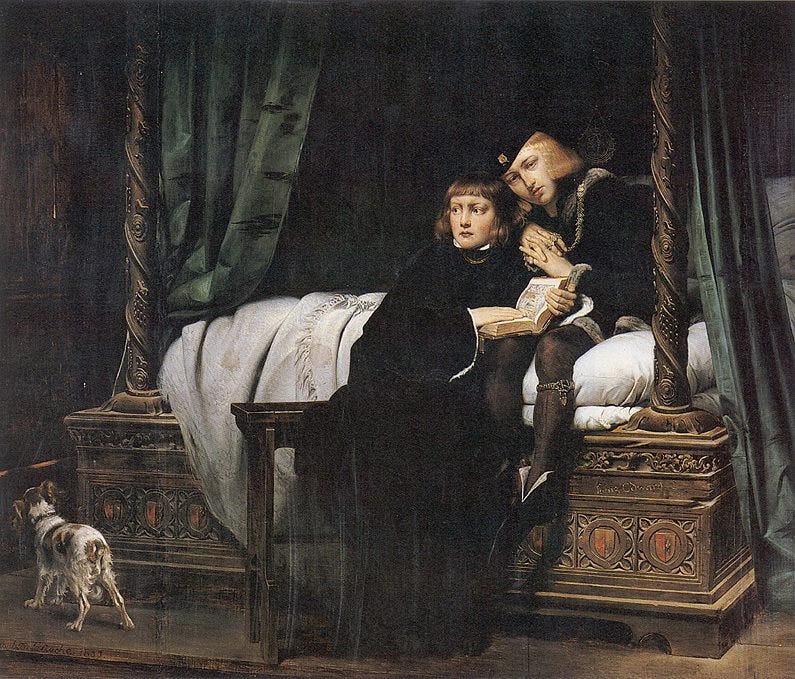

This man did not hold the child for any depravity, rather caught her there for fear, that she had somehow come into his possession years ago, the girl had long forgot herself, the man barely seemed to care, but the fact remained that she had seen him, that was too much, that she had been here now too long, that yet he could not kill her, had tried once or twice, that he simply could not, and so he put up with her and she, in her way, with him. The fact was that she loved the man, had always, and this from the moment she first saw him, even knowing what he was, even along with all she saw then and since, that she loved the man with the simple purity only possible of a child, not of some suffering syndrome, not some cause that need be explained by psychiatrists in a court case of later years, rather with all the simplicity of an angel, that there was in this quiet love a perfection, despite the dark.

The man himself did not love, did not know love, perhaps never had. Those that he loved, those that he spoke of as loving, for whom he wailed, they were always absent, having all abandoned him whether by death or more ordinary means, that these alone were those for which he knew love, and there was a truth in this love, that the depth of affect itself was beyond certain, and yet—and yet there was something in this, for there were those alike who loved and offered presence, but these were never the objects of his love, it was rather always the absent that he loved, and this perhaps for the fact of their lesser demands, and this alike for the fact of their increased suffering, for the child saw with sadness that what the man really loved was his own pain. He loved himself and could only love others to the extent that they heightened his sense of self, and so the stark absence of these various loves served as a tuning fork that set him vibrating in such a fashion that he felt himself alive, for which reason alike they had a tendency to leave him, not that the deaths could be blamed on him, however fortunate.

There was alongside this only the violence, that and the hollowness which reigned between, that his days were spent in transit between these two queens, emptiness and despair. The latter came in its flavours, first the silent scream, the suffering of absence, the pleasure of this, and then the frantic flailing, the dancer madcap frenetic, whatever shapes would bend or twist his brain into something resembling feeling, would contort him into strange shapes, not always pleasant, not always anything at all, long hours spent staring at walls in day-drunk states, yet all of this, the raging which came in early mornings left along, the fear which followed, the sickness—that again here in the simple necessity of this, in its waxing and waning, in the immediate demands it made, that here there was all the concreteness of a life which was for him otherwise foreign.

The child would hear all of this, its varied sounds, would hear this and understand, and this in a way without words, would understand that he was missing something, and in the tenderness she felt for him, in the simplicity of love, in that love which overcame all disgust, all fear, all that would be thought appropriate for the state of one imprisoned in the dark below, that cared not for the stench which emanated from the house, for the rot which ate away at him, which knew none of this but for that simple love—that somehow if she could only communicate this to him, could only take his hand, then it would all be washed away, then if he could see himself in her eyes, then if he could only see another person, for she felt, and this again in the sense of a child known without words, that she felt this was the core of his isolation, that he was imprisoned alike with her, and if only somehow he could see himself, could see another person, then he might not be so alone.

The man did not come to the stairs anymore, some weeks had passed now. Water dripped from a crack in the wall, tasted of mortar and left a grit in her mouth, coated her gums strangely, that there was this water which she lapped from the wall, but there was no food.